Granada Old Town

The historic center of Granada keeps true jewels, authentic heritage treasures you should not miss. Check everything you must see in Granada old town and prepare yourself to enjoy.

Index

- Granada Cathedral

- Royal Chapel

- Madrasa

- Alcaiceria

- Bib Rambla Square

- Corral del Carbon

- Plaza Nueva Square

- Real Chancillería and Royal Jail

- City Hall and Plaza del Carmen

- Calle Elvira Street

- Medieval Merchants’ Exchange Market

- Church of Santa Ana

- Gran Vía

- Bishop’s Palace

- Centro José Guerrero

- Main Mosque Cistern

- Monument to Queen Isabella I of Castile and Christopher Columbus

Granada Cathedral

Granada Cathedral is one of the symbols of the Renaissance in Granada and along with the Charles V Palace and the main Altar of Saint Jerónimo is one of its best examples in the city. The monument can be visited on our Private tour to the interior of the Cathedral and Royal Royal Chapel of Granada.

Inside the Granada Cathedral

Despite its initial design following a conventionally Gothic style, the inclusion of Diego de Siloé as the lead architect soon meant a major change in style for the project, moving towards a something completely renovated and new, both structurally and aesthetically.

Already considered an eighth wonder of the world in the 16th century, and with the site initially chosen to be Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s burial ground (despite not having happened eventually), it is particularly important as far as architecture in Granada and has a beauty and magnitude that no one visiting the city should miss out on experiencing.

The beginnings of the building of the Cathedral date back to 1506: the year when the first project for it was conceived by architect Enrique de Egas. This already planned on the Royal Chapel being incorporated as an annex. As a result of the death of Queen Isabella in 1504, the building of the Royal Chapel had to be started first, so it would not be until 25 March 1523 when the first stone of the cathedral was set.

Just three years later, the arrival of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V brought about a new change in the building plans, since the Emperor wanted the Cathedral to be his burial site. Despite this decision being postponed, at the time it meant the dismissal of the original architect and the addition of Diego de Siloé as master builder.

Alonso Cano in Granada Cathedral

The new design had to combine the functions of the church and imperial pantheon in such a way that Siloé’s project ended up being much more structurally and aesthetically complex than his predecessor’s. However, we can say that he was truly the great architect of the Cathedral, of course, with the help from other renowned artists such as Granada resident Alonso Cano.

The new project followed the classical Roman traditional style, adding a basilical ground plan with a circular apse as a mausoleum, far from the original Gothic-style design. Siloé worked consciously on the aesthetic additions to the cathedral. An example of them is the addition of important ornamental elements to its architectural structure such as the façade of the Ecce Homo, the fácade of Saint Jerónimo, the façade providing access to the Sacristy or the façade of the Perdón.

In 1563 Siloé died and his work was left to his beloved disciple: Juan de Maeda. However, twelve years later, Juan was required to stop the construction, because of the crisis resulting from the Moorish rebellion in 1568. Thirteen years would then go by until 1581 when Ambrosio de Vico took over construction. In 1667 the great façade was begun by Alonso Cano and in 1704 construction was finally finished.

However, its structure would undergo further changes later on. The most important of them took place in 1926, when chancel was eliminated and the later had its decorations moved to other areas of the Cathedral, which completely changed its spacial distribution, turning it into a great airy space.

Since the 16th century, and with the main chapel having just been finished, the Granada Cathedral has been considered an architectural benchmark, with many of its elements being prototypes for later construction projects and due to which, numerous architects came to learn and perfect their knowledge and craft.

From the outside, the tower is worth mentioning, which (though incomplete) is one of its main elements due to its large scale. It takes up the corner between the north and main façade and is organised into floors following the traditional order, that is to say, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. It has three sections successively done by Siloé, Madea and Vico. The Cathedral Museum today is located in the lower one.

Its main entrance is especially important, work of the great Alonso Cano, designed as a great triumphant arch with three high arches and decorated with marble reliefs of a number of evangelist virgins and figures. Its main relief of the Incarnation is the work of other local artists such as José Risueño. Inside, its main chapel is especially important, even if the whole interior of the cathedral lets us appreciate the important and innovative contributions, especially by Siloé, which make the Cathedral such an important and significant building.

Main Grille of the main chapel of the Granada Cathedral

The main chapel stands out in particular due to its size and its amount of open space, with a diameter of 22 metres and an innovative arrangement in the form of broad circle, which meant being able to worship from many different parts of the building, while in the rest of medieval cathedrals there is an apse arrangement. A tabernacle dominates it, which was a gift from the duke of Saint Pedro de Galatino and the Crown, a great vault representing the heavens, decorated with golden stars and resting upon a series of two-storey Corinthian columns.

On these floors a series of arched panels are divided which separates the paintings below from the stained glass above, becoming an enormous and magnificent iconographic medium where we can admire scenes from the Life of the Virgin, of the Birth of Christ and the Passion of Christ.

The main chapel also includes important sculptures such as the figures of the Apostles (also in gilded polychrome), the busts of Adam and Eve by Alonso Cano and the large figures of the Catholic Monarchs praying.

Despite how stunning the main chapel is, make sure to pay attention to the rest of the chapels in the ambulatory where you will find numerous pieces by Granada artists, such as Pedro Duque Cornejo; the chapel of Saint Lucia, with the sculpture of it by Alonso Mena; the chapel of Saint Cecilio, or the magnificent reredos of the Triunfo de Santiago, by Hurtado Izquierdo.

Other notable parts of the interior of the cathedral which is worth checking out include the paintings by Juan de Sevilla and Pedro Atansio Bocanegra located on the stone reredos of the decoration, on the transept, as well as the work on the side chapels (much of it also by local artists) such as the Cristo de la Esperanza by Pablo de Rojas or the old pulpitum, disassembled and housed in the chapel which has been home to the figure of Nuestra Señora de las Angustias since eliminating the chancel in 1926, designed by José de Bada and done with marble from local quarries.

Royal Chapel

The Royal Chapel (Capilla Real) as far as art is concerned represents the transition from the Medieval to Modern period, just as the Catholic Monarchs represent this for the transformation of Spain. In its composition we can appreciate how the first Renaissance detailing contrasts with the late, already disappearing, Gothic style. The monument can be visited on our Guided Tour of the Cathedral and the Royal Chapel.

The founding of the Royal Chapel takes us back to 1504, as confirmed in Queen Isabella of Spain’s will on October of the same year, a month before her death. In the beginning, the planning of the building, right in the heart of Granada, was left to Enrique de Egas in 1506, who, influenced by Cardinal Cisneros, committed to creating this extremely austere building. Furthermore, it was decided that the chapel should form part of the future Cathedral of Granada both physically as well as aesthetically.

It was institutionally completed in 1517. It is worth pointing out as far as its ornamental richness that the work carried out in the Tomb of the founding kings by Domenico Fancelli; later the work of Bartolomé Ordoñez for Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad, as well as the series of work done after the arrival of Charles V, which was influenced by theories of new humanism. The early contributions were by artists such as Fancelli, Ordoñez, Bigarny and Jacobo Florentino, although they would be reinforced by the work of two of the main artists from the Granada School of the 16th century, Pedro Machuca and Diego de Siloé.

Inside the chapel you can see some of the interior walls almost completely devoid of decoration, adorned with a wide frieze alluding to the Conquest of Granada, the death of the Monarchs and the completion of the chapel, in Isabelian Gothic style. Just like on the building’s exterior, the royal heraldry can be seen repeatedly throughout the chapel.

Inside, it stands out both for its novelty and artistic mastery; the tombs, the main grille and main reredos are true benchmarks in Spanish and international art.

The Tomb of the Catholic Monarchs

The tomb of the Catholic Monarchs was sculpted by the Italian Domenico Fancelli and is a particularly unique piece as far as funeral sculpture during the Spanish Renaissance was concerned.

On the slabs, the reclining figures of the Catholic Monarchs presents Ferdinand to us as a soldier, with a sword, cuirass and cape. Isabella, with her courtier attire, is presented without any commanding characteristics. On the other hand, the tombs of Philip the Handsome and Joanna the Mad work by sculptor Bartolomé Ordoñez, show a more ostentatious style and make heavier use of sculptural and sensitive elements.

Main Grille of the Royal Chapel

This wonderful grille is the work of master grille creator Bartolomé (Bartolomé de Jaén), one of the all-time most important representatives in this field.

A large coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs accompanied by the characteristic emblems of the yolk and arrows takes up the second middle section. On the sides, the two Apostles with their characteristic features and on the upper part of the gapped cresting, topped off in this case with scenes of the Passion of Christ that Bartolomé himself decided to add even though it was not part of the original idea. All of this was embossed and chiselled on both sides and accompanied by stunning colour work that makes it particularly impressive.

Main Reredos of the Royal Chapel

On this reredos, which is the work of French Sculptor Felipe Bigarny, we can appreciate the inclusion of a collection of reliefs that recall the surrender of Granada. Placed on the lowest part of the reredos, at the front of the altar, we are presented with the Surrender of Granada (the royal party and Boabdil handing over the keys at the Puerta de la Justicia. On both sides, two ledges hold up the praying figures of Ferdinand and Isabella, safeguarded by Saint Jorge and Saint Juan, patron protectors of the monarchs.

Inside the chapel there are many other interesting pieces, many of which done by renowned local artists, such as is the case for the doors of the sacristy, a piece by Jacobo Florentino.

Treasure of the Sacristy

The Catholic Monarchs, and more specifically Isabella, wanted some of her personal objects placed next to their bodies in the chapel. To do so, a museum was opened in the sacristy were some of the main pieces on display such as Ferdinand’s sword or the middle of Isabella’s crown.

The collection of paintings is also noteworthy since the queen’s Flemish panel painting collection was the largest at the time. Among these paintings we find pieces from the first Flemish school (by artists such as Rogier van der Weyden or Hans Menling) next to other pieces from the Spanish school (for example by Bartolomé Bermejo) and the Oración del Huerto, attributed to Boticelli.

Madraza

The Madraza (Madrasa) was built in the year 1349 by Yusuf I under the name Madrasa Yusifiyya. It was first centre for Koranic studies, the only one in Spanish territory during the Al-Andalus period. The sultan built the Madrasa in an artistic golden age for the city of Granada, next to other emblematic buildings such as the Maristan and the Corral del Carbon, which are also located in the main areas of Granada’s old medina.

In the beginning, the Madrasa was symbolic of the importance of Granada as Al-Andalus’s cultural capital. Its prestige meant that the most brilliant minds in the Islamic world, masters in scientific, philological and literary disciplines would carry out their work within its walls.

However, starting in 1492, the arrival of the Catholic Monarchs would lead to a radical change in the building’s functions, with it becoming the headquarters of the Council of Granada. The Cathedral of Granada and the Royal Chapel were built in the vicinity. Its new purpose resulted in a series of additions and renovations as far as its original planning: in 1501 an adjacent house was added that had been property of Prince Ferdinand of Granada (the converted prince Nasr, the son of the sultan Muley Hacén and Soraya). The addition would give rise to the current Hall of Knights Twenty-four or Winter Chapter Hall.

From Madrasa to the Old City Hall

At the start of the 18th century the building was almost totally rebuilt. With the exception of an Arabic oratory which stayed hidden, the initial Islamic Madrasa was gotten rid of to make way for a new civil complex in the Late Baroque style. In 1858 City Council moved to its current location, the Carmen Convent, after which the Madrasa became property of the Echevarría family. The state acquired it in 1939, and from the 1940s onwards it was ceded to the University for institutional purposes.

Of its Islamic past remains the Nasrid praying room, a characteristic qubba with a square design with precious ornaments: mullioned windows, an alicer of muqarnas, and even some of the original plasterwork.

In the Hall of Knights Twenty-four, on the upper floor there is a preserved Mudejar frame which survived the renovations over the last few centuries. One can also appreciate the doors which formed a part of the old City Hall Chapel.

The main façade is one of the main works of Granada Urban Baroque architecture, an impressive pictorial façade which imitates blocks of stone covered in dark grey marble.

The chapel of this monument is part of our Essential Granada Private Tour and the Hall of Knights Twenty-four is a part of our Places of the Catholic Queen Isabella I in Granada private tour.

Alcaiceria

Alcaiceria is derived from “al-Kaysariyya” in Arabic, referring to the payment of duties to the Caesar (or Byzantine Emperor) for the trade and custody of valuable goods. There were a number of alcaicerias in Islamic Spain (in Toledo, Cordoba, Seville, Valencia, Palma, Malaga, Almeria and Velez-Malaga), but only the one in Granada survived, even if after the 1843 fire it was rebuilt. It was established back in the Nazrid period, with the first information we have on it alluding to the mid-15th century. The Alcaiceria in Granada was home to the important business of the silk trade, the most important industry in Granada in the Nazrid period.

The Alcaiceria in Granada was erected right in the heart of the Islamic medina, close to the Aljama mosque, in an area brimming with goods, similar to a traditional souk.

Andrea Navaggiero described it as follows: “An enclosed space with many narrow streets all over filled with shops, where the Moorish sell silk and an endless amount of knick-knacks; it’s like us having a haberdashery or a Rialto and there are hundreds of things, especially made from worked silk”.

In the 16th century there were around 200 shops. It was accessed by a set of eight gates. The Granada-style cobbled streets were narrow and left one with the feeling they were in a labyrinth. The appearance of the shops must have been motley, lacking clear architectural cohesion: cramped single-story spaces that opened onto the street with wooden setups that could be taken- or pulled down from the ceiling using an iron rod. The shops were so small that “the owner sitting in the middle could reach any object with their hands without even having to get up”.

Its current appearance is a consequence of a terrible event which took place early in the morning on 20 July 1843: a voracious fire over the course of six hours completely destroyed the area. The rebuilding of the Alcaiceria was undertaken immediately, and today it is an interesting adaptation of Neo-Arabic architecture to 19th century commercial interests, being closer at its core to a souk.

It is just this commercial and handicraft souk aspect that breathes life into this unique space, a starting point for new bazaars featuring jewellery, bronze, inlays, pottery, etc. invigorating this market with colour and life.

This monument is a part of the route for our Essential Granada Private tour.

Plaza Bib Rambla

The Plaza Bib Rambla (Bibarrambla Square) has always been the “main one”. It is the closest thing Granada has to a Spanish and Andalusian style main square, although lacking a colonnade and public buildings. This is due to the fact that what we are really dealing with is one of the most transformed spaces in the city. Its image reflects the most important parts of Granada’s urban history.

It dates back to the Nasrid period when it was an open space linked to the main gates of the city: the Bib al-Ramla or Sand Gate. The space must have played an important role as it was close to both the great mosque and the commercial hub of the Zacatin which supplied the medina.

The area would have been small by Spanish standards, as far as traditional and lifestyle requirements go. Due to its excellent location and the possibility of expansion, it was subjected to reforms shortly after the surrender of the city around 1495, when it began to be referred to as the New Bibarrambla Square. In 1505 King Ferdinand the Catholic ceded it to the city as a place to walk around and conduct business in, but since it was still rather small, the count of Tendilla ordered the demolition of a number of houses. Between 1516 and 1519, the square began to be expanded in a more orderly way. After Bibarrambla was renovated it would near its current size.

It was a large rectangle that could be accessed via a number of narrow streets in the corners, except the Spoon Arch -opened in 1519 to connect to Mesones Street-. The western side, parallel to the Nasrid wall was home to the Miradores council house, the count of Tendilla’s houses and other buildings related to the Inquisition, with windows or verandas. The opposite side was taken up by the University -today the Curia-, the Archbishop’s palace and the Alcaiceria’s shops.

Bibrambla Square as public celebration area

From the start of the 16th century, it was the city’s main celebration area for public festivities: equestrian games, bull and cane festivals, Corpus Christi, processions, poetic games, auto-de-fés, royal proclamations, greeting archbishops and even for public executions. It was also the main public area for street vending, which in the 18th century reached a peak of 54 wooden stands selling fruit and vegetables.

In 1880 a small garden was created and fenced in, making way for the monument of Fray Luis de Granada, which today is found in Saint Domingo Square. The final work on it was overseen by the government of Gallego and Burín in the 1940s. A number of luscious lime trees were also planted at that time and it recovered its commercial role with stands, which today blend in with the square’s lamp shop, with the Sevillian smelting of the Perez Brothers, who moved to Granada after the Seville World’s Fair in 1892.

These days Bibarrambla continues to be an important place for celebrations, for local festivities such as the Cross Day, and above all, as the stage for Las Carocas of Corpus Christi Day and Tarasca procession.

Giants Fountain in Bib Rambla Square

The most impressive fountain in Granada centres Bibarrambla, even though it was not originally intended for public use, and was in fact made for the cloister of the now in-existent Agustinos Calzados Convent. It was taken down from the cloister of Saint Agustín, and after making a variety of stops in other squares and places in the city, arrived at its current location in Bib-Rambla Square.

The first circular cup, resting on the cervix of four anthropomorphic beings. These nude “Gigantones” (giants) give the fountain its popular name. This holds up the white marble sculpture of Neptune, with his trident in one hand and the other raised making a greeting gesture.

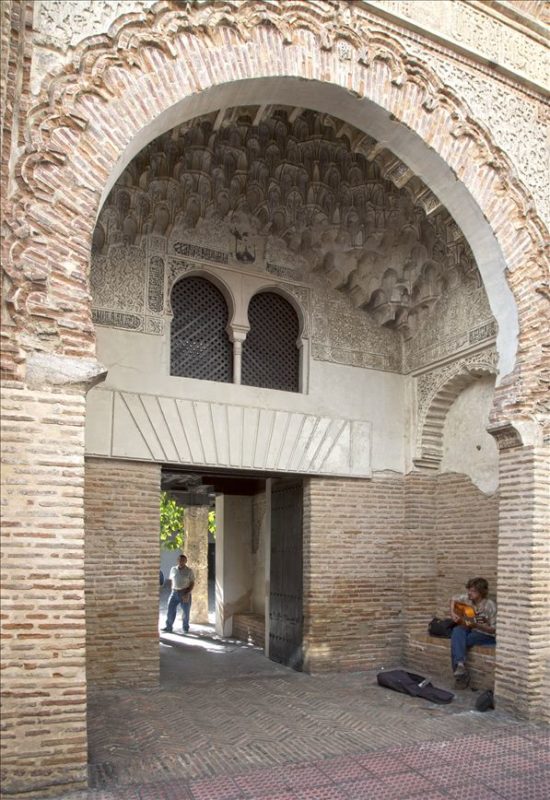

Corral del Carbón

The Corral del Carbón (Corral del Carbón) is many things, but one of them is it being the only Nasrid alhondiga preserved in its entirety on the Iberian Peninsula. Originally the building was a true Kahn or Caravanserai, for storing goods, although over the centuries it was adapted for a number of different uses, among them, being used as a storehouse for grain and coal, small apartments with a central courtyard and an Open-Air Comedy Theatre. The monument can be visited as a part of our Essential Granada Private tour.

It is one of the most important buildings preserved from Granada’s Nasrid period, and its survival is owed to the multiple uses it has had throughout history. The Corral of Coal was built in the 16th century as a Khan or Caravanserai, a characteristic building in Muslim medieval medinas, in the middle of their commercial area. Its original name is al-fundaq al-yayida or New Alhóndiga, and in fact is the only preserved Alhóndiga from the Al-Andalus Nasrid period. The name Corral of Coal already showed up in 1531, due to its use as a storage facility for coal.

Its survival to the present day is due to being adapted for multiple uses over the centuries. Starting in the 16th century it was turned into an Open-Air Comedy Theatre, and from the 17th century onwards it was transformed into small apartments with a central courtyard.

It has an impressive façade made with a large horseshoe arch. The arch, pointed with brick keystones, is decorated with a number of small lobed arches carved in plaster that make up complex and gorgeous lattice work. It was originally painted in variety of colours. A mullioned window dominates it on a narrow central column with a sebka strip on each side.

This arch gives way to a vestibule with benches on the sides, on which there are a number of decorated arches with arabesque motifs that are covered with a vault of muqarnas. Once inside the alhóndiga you can go to a square courtyard with three floors. In the centre of the courtyard there is a preserved stone tub from the initial construction.

Currently the Corral of Coal houses the technical office for the Granada International Festival of Music and Dance, as well as being a place for cultural activity in the city, where there are a lot of shows such as music and dance recitals as well as theatre, especially in summer months.

Plaza Nueva

The public square, which is now known as Plaza Nueva square, is the result of a long and drawn out evolution. It is unique in the history of the city of Granada, because it started at the beginning of the 16th century and continued until the middle of the 20th.

It is an urban settlement that has adhered to two premises: the progressive covering over of the Darro River, which starts its hidden trajectory in this square through the historic centre of Granada until flowing out into the Genil river, and the concurrent appropriation of land belonging to a collection of surrounding country houses which, after a number of successive dispossession operations, made way for the continuous growth of the square until it attained its current size. It is not, however, a square which was built all at once, following prior planning, but rather the opposite. Its form has been the end result of diverse historic circumstances which determined its evolution to date.

After the Conquest of Granada and as a result of the heritage bequeathed by Muslim-style urban planning, the city’s design lacked open areas which could satisfy the social needs of local inhabitants. The building of Plaza Nueva Square was an initiative driven by City Hall, and is therefore the first major city development project which would result in overcoming the lack of open squares and create a space which would be emblematic of Granada’s new image as a Spanish city.

Plaza Nueva Square between Albayzin and Alhambra

Plaza Nueva Square was the nerve centre of the modern city since it connects the three main areas which had made up Nasrid Granada: the medina, the Alcazaba Qadima, located in the neighbourhood of the Albayzin and the Alhambra, via the road leading up to it, the Gomérez Slope.

However, beyond its undeniable centrality, the main role Plaza Nueva Square has played in Granada is understood through looking at the important and diverse civic activities occurring there: a recreational area for jousting, tournaments, cane and bull games as well as other celebrations; being a grim location for public executions, as can be noted by the gallows depicted on the Platform of Granada by Ambrosio de Vico; a formal stage for celebrating proclamations, royal weddings and royal birthdays, military victories or religious holidays, and coming and goings from the Royal High Court (Real Chancillería).

A number of decades later, coinciding with the building of the Royal High Court, Plaza Nueva Square del Hattabin was to be expanded with a second vaulted area. The decision to start construction on this was justified on the grounds that the Royal High Court would then have the proper urban framework which its high prestige as the legal body of State Administration demanded, providing enough perspective to take in its noble façade.

The public fountain, initially installed in front of the Royal High Court, was later moved to its current position. The fountain is completed with a pomegranate.

This monument is included on the route of our Essential Granada private tour and private tour of the Albaicín and Sacromonte.

Real Chancillería and Royal Jail

The establishment of the Real Chancilleria (Royal High Court) in Granada was a part of the programme promoted by the Spanish Monarchy for settling the city, after the conquest, with prominent public institutions.

Prior to its establishment, the Catholic Monarchs had sponsored an important judicial reform through which the Royal Audience of Castile was divided into two chanceries, one with its seat in Valladolid and the other in Ciudad Real. Legal authority was distributed between both chanceries, and the move of the chancery from Ciudad Real to Granada did not occur until 1505.

Initially it was established in the Alhambra, but Emperor Charles V, during his stay in the city, ordered it moved to the city as well as the construction of the current building.

Royal High Court, symbol of Christian Granada

The Mannerist-style façade of the Chancilleria is an exceptional contribution to public architecture during the reign of Philip II. To make it a reality, a call for tenders was organised. The façade, conceived as a genuine symbol of power, reflected the presence of the Crown in the city. It is organised into two horizontal sections for two stories and seven vertical panels. The façade was finished by a large entablature with a stone balustrade on it with a pyramid finish, five on each side of the main entrance. On top of there is an iron cupola that protects a clock. The result is an admirably elegant and beautiful façade.

The courtyard, attributed to Diego de Siloé, has half arches held up by high Tuscan pillars made of white marble. Of a total of sixteen medallions on the portico, twelve contain representations of masculine figures from Antiquity, most of them Roman generals and emperors, while the four remaining ones are feminine figures, three of them Roman matrons.

The great stairway provides access to the upper floor that, just like the façade, was created during the reign of Phillip II. Today, the building is the seat of the High Court of Justice of Andalusia.

The Royal High Court is included as a part of the route for our Granada Must-Do Tour.

City Hall and Plaza del Carmen

Granada City Hall’s current building, located in the centrally located Plaza del Carmen (Carmen Square), is an interesting place that over time has gone through numerous transformations, trials and tribulations. Its story began as the home of the convent of the male Carmelites.

Initially, a first arcaded cloister was built, an area that does not exist anymore referred to as the “old cloister” which took up the area where the Carmen Square currently is. A main cloister, called the “new cloister”, was larger than the first one. This is the only part of the convent’s building that has been preserved, and now holds City Hall’s courtyard.

After the confiscation of the building, the church was demolished. As for the convent, it was ceded in 1848 by the State to the Municipal Government for the purpose of moving the Casa del Cabildo to it. Due to the lack of funds for undertaking the renovations on the building, the Municipal Government made the decision to knock down the old cloister in order to reduce the costs of the change, placing a new representative square in the space the old cloister previously took up.

At the start of the 20th century, the municipal architect Modesto Cendoya led the remodelling of the façade, in keeping with design standards of the time, and built the majestic stairway that provides access to the first floor.

The equestrian statue of the precise moment was placed on the middle of the roof. This beautiful sculptural group of polished patina-finished bronze sitting atop the main façade of City Hall was entrusted to Guillermo Pérez Villalta to commemorate the fifth centenary of the Municipal Government of Granada. The piece depicts a horse in motion with three of its legs on golden spheres and a nude rider mounted on the horse’s hind-quarters, wearing a blindfold and holding a fourth sphere in his right hand.

The piece was conceived as a symbol of happiness, representing the achievement of a moment of triumph, of perfect, yet fleeting, balance. A moment you are only aware of when it has already gone by and the blindfold covering our eyes falls. The material execution of the piece was done by sculptor Ramiro Mejías.

This monument is a part of our Private places of Isabella the Catholic in Granada tour.

Calle Elvira

Calle Elvira (Elvira Street) – the Muslim zanagat Ilbira– was the main and longest street in Islamic Granada from its development in the 11th century. It started at the Puerta Elvira (Elvira door), in the northern part of the Medina’s walled area, and reached the heart of the same area where it ended at the then uncovered river, the Darro river.

In the beginning, it was a street with an even more irregular and narrow shape than it has today. Despite its lack of width, the street was notably wider than those in the surrounding urban area, characteristic of medieval Muslim cities, which combined with its considerable length and strategic location from the very beginning turned it into a key artery for the development of flows of people and goods in the city, and as a result, for the busy commercial activity being established down it.

Elvira Street: The urban meeting point of Muslim and Christian Granada.

Elvira Street intersected Calle Zacatín, the other major commercial artery of the medina, since up to the end of the 19th century, that street was longer than at present; until the development of Gran Vía of Columbus entailed the elimination of around half its length.

The opening of Gran Vía meant Elvira Street would definitively lose its historical role as the main transit route in the city and would now have a secondary role in the urban structure in the city centre.

Along it there are landmarks that bear witness to the urban importance the street had in the past. The street starts with the monumental Elvira door and there is another historic structure of Muslim architecture nearby, El Baño Hernando de Zafra, as well as a number of Christian buildings such as the Parish church of Saint Andrew and the church of Los Hospitalicos.

This street is a part of our Essential Granada private tour.

Medieval Merchants’ Exchange Market

Attached at the feet of the Royal Chapel and as a vestibule for visiting it, you’ll find what originally was the Lonja de Mercederes (Medieval Merchants’ Exchange Market), one of the clearest examples of late Gothic civil architecture in Granada.

The decision to build a market was made by the Municipal Government in 1518, as house of trade for merchant meetings and business and for checking precision of the weights and measures.

Furthermore, a special bank specifically linked to the silk trade was established, since this was a key commodity in Granada’s economy in the 14th and 15th centuries located in the Alcaicería.

Choosing a location would be based, firstly, on being close to City Hall (then located in the Palacio de la Madraza) and secondly, on being at the heart of the city’s commercial and financial activity.

The original project, later modified, consisted of a one story rectangular building open to outside with high arches. It is believed that the initial project must have been done by Enrique Egas, as an extension of the first project of the Cathedral-Royal Chapel.

Building the Medieval Market

There was strong opposition to its construction by the Royal Chapel, which argued it was owner of the land and that the proximity of commercial activity would be disadvantageous for religious activity. Faced with a lawsuit resulting from the dispute, the Chancilleria adopted a reconciliatory agreement that approved the construction of the market, but the Royal Chapel was allowed to build a second floor on top of it for its own use. The building is fairly small compared to typical market exchange buildings from the time period.

The municipal government soon gave up the idea of establishing a market exchange building here and after a variety of uses, in the 18th century it was sold as a private building.

At the end of the same century it was purchased by the archbishop in order to house the Diocesan Museum, and at present, it is the archive and library for the Royal Chapel.

The current state of the lower part is completely see-through, partially opening the exterior arches with smooth glass, due to a recent restoration headed by Pedro Salmerón Escobar. The hall is now used as an entrance lobby for the chapel, which has entailed adding some furniture, portraits of kings and a copy done by Manuel Gómez-Moreno of the painting of the Rendición de Granada (Surrender of Granada) by Franciso Pradilla. The coffered ceiling on the lower floor stands out in particular.

The Medieval Merchants’ Exchange Market is a part of the route for our Essential Granada private tour.

Church of Saint Ana

Towering over the popular Plaza Nueva Square in Granada, the Church of Saint Ana was erected upon the ancient Zirid mosque known as the Aljama of Almanzora. The construction of the church kicked off in 1537 and 1540, in accordance with a project by Diego de Siloé.

The façade, preceded by the church’s barred atrium is made of brick, and its portal and beautiful tower are especially noteworthy. The construction of the splendid brick bell tower consists of three bodies decorated with blue and white ceramic glazed tiles.

The interior contains a single nave, typical in 16th century Granadian parishl churches, with side chapels and a very wide apse, a beautiful rectangular armor.

Among the many works preserved in the nave of the church, are some by relevant Granadian artists: a 16th Century Calvary by Diego de Aranda; two carvings by José de Mora (La Soledad is one of the masterpieces of Granadian Baroque statuary); and the Virgen de la Esperanza by José Risueño, the most beautifully dressed dolorosa of Granada, which parades alongside the Nazarene of Great Power in the Brotherhood of Hope.

On the other hand, the major chapel contains the carvings of Saint Jerónimo, by Risueño; of Saint Juan de Dios, by Diego de Mora; as well as a canvas of the Birth of the Virgin, by Pedro Atanasio de Bocanegra.

This monument is also included in the Essential Granada private tour.

Gran Vía

Gran Vía of Columbus: The building of a modern street in the historic centre of Granada.

Gran Vía is currently an exceptional catalogue of Granada architecture from the first third of the 20th century. In addition it is also the main route through the historic centre. Walking down it today is a wonderful experience that adds to the other historic areas of the city.

Gran Vía of Columbus, is a street that now-a-days offers up an exceptional bourgeois Granada architectural heritage. Since the inauguration of the Train Station Andaluces in 1874, the logical increase in the movement of people and goods started to require the creation of a quick and direct transport link between this point and the centre of Granada. At first, this traffic circulation role had to be provided by Elvira Street, which, turned out to be clearly incapable of allowing a fluid flow of traffic on it.

The establishing of ten sugar factories dedicated to the production of beet sugar started to produce continuous movement activity which made it of urgent importance to one way or another implement an urban planning project that would adequately improve transport in the city. The impetus to get the initiative off the ground did not come from Granada’s municipal government, but rather from an eminent Granada resident that knew how private initiatives worked and who embodied the new spirit of bourgeois progress. Juan López-Rubio Pérez, the creator of the first beet sugar factory in the Vega.

Juan López-Rubio, then President of the Granada Chamber of Commerce and Industry, proposed an initiative conceived as a business, but also as a wealth generating project for the city. It was the construction of a new street, a major road or –gran vía– that, similar to those created in other European cities following the model of the Parisian avenues and boulevards of the 2nd French Empire, promoted improvements in transit, hygiene and public decoration, while creating new jobs in the city.

The Gran Vía project implied a radical change as far as the urban planning practices which had been applied in Granada in the previous decades. It was not about promoting an urban stretch of road through a new operation of extending a street, widening it and making the previously existing one more uniform; but rather opening up a new one, breaking the historic routing through a major operation of expropriation and demolition of houses and other buildings.

The new street was to be called Gran Vía of Columbus and was to be inaugurated in 1892, coinciding with the four-hundred year anniversary of the conquest of Granada and the Discovery of America.

This was to be a 20-metre wide street. The architect Modesto Cendoya was mandated to draw up the project for the new street. However, it took two more years for the Gran Vía of Colombus project to be declared in the public interest and receive the necessary government approval. From then on, the festivities for the Fourth Centenary had already come and gone, but what is important is that, despite the delays, the municipal government then was ready to proceed with the construction work needed to build Gran Vía.

There was no opposition to the project at that time or in the many years needed to carry it out, at least, no one dared to publicly protest amidst the general opinion that the works were the symbol of progress the city aspired to. It was not until the project was quite far along and close to being finished that the first opposition was heard (from Angel Ganivet, Federico García Lorca and Leopoldo Torres Balbás among others), who lamented the disappearance of the old Granada before a street now marked as a vulgar copy of urban planning and architecture brought in from elsewhere. A critique than finished by dividing Granada residents for a long time and that has only recently been overcome due to the importance of the heritage of the triumphant bourgeois who wanted to show signs of progress using Gran Vía as the medium.

Bishop’s Palace

Bishops’ Palace, first Literary University, is placed in a great building from the 16th century. This was the first site of the University of Granada, built by Emperor Charles V in 1526. Its founding took place in the context of a conflictive relationship with the Moorish in the Kingdom of Granada, accepting the teaching route as an effective way to integrate them.

In 1767, the university moved to the Old college of the Society of Jesus. Today the building is part of the Faculty of Law.

The first building was then turned into the site of the Curia, the ecclesiastical court with bureaucratic, administrative and judicial functions. To that end, necessary renovations were carried out and it was connected to neighbouring the Archbishop’s Palace.

The University of Granada was conceived from the start according to thinking of Alcalá de Henares, as a general university studying associated with a hall of residence. Of its three façades only the main one, facing the cathedral, is architecturally important, given that the side was functionally opened to the Pasiegas Square at the end of the 17th century, and the façade of the Catalino School only had a small door, given that the Granada council was not very inclined to let the students leave through it and get distracted by the racket in Bibarrambla Square.

Distribution of the rooms in the Curia

In general, and despite the changes in use over its history, the building has kept its internal organisation, except for the connection with the Archbishop’s Palace, as in the 18th century both buildings were connected and a secondary staircase was built. The ground floor of the building had the classrooms for Grammar and Law and Canons to the left. The right part of the hall has another Grammar classroom in the eastern corridor and the Grand Hall. On the first floor there was a hall of secret acts or General Alto and library, the rectory, the cloisters hall and ¡Philosophy- Medicine- and Theology classrooms as well as the chapel.

This large complex of rooms shows a rich repertoire of Moorish panelled ceilings. Finally, as a historical way of remembering of the post-secondary evolution of the building, it is worth mentioning the recovery of some of the cheers from students after receiving their degrees, featured on the walls surrounding the galleries of the courtyard.

The Curia and the Archbishop’s Palace are a part of the route for our Essential Granada private tour.

José Guerrero Centre

This institution adds a touch of modernity to the monumental center. Created to host a foundation dedicated to the most universal Granadian artist of the 20th century, José Guerrero. The heirs liked the property, as it could be seamlessly refurbished and it reminded them of the industrial buildings he used as studios in Soho, New York.

This contemporary art museum was inaugurated in 2000. The rooms are ideal for a serene and evocative contemplation of the exhibited works of art, and the upper floor contains a surprise: a glass surface frames a view of the cathedral complex as if it were another painting hanging on a transparent wall.

The Center counts with a selection of 40 paintings that belonged to the artist’s personal heritage, as well as a wide variety of works on paper and a very rich personal archive.

The Collection spans from the mid-40s to 1990, including key works of the artist’s oeuvre: from his learning years in Paris, to the lively impression America made on him, and the transcription of ordered chromatic experiences from the Seventies onwards, to be found in his arches and matchboxes. A fundamental work is La brecha de Víznar, dedicated to the death of Federico Garcia Lorca.

In our Essential Granada private tour we walk just by the door of this center.

Main Mosque Cistern

In the corner made by the façade of the Merchant’s Market and the Royal Chapel, next to the façade, there is a small parapet behind iron bars. This is the only visible part of the aljibe (cistern) that belonged to the main mosque of Medinat Garnata.

Granada is particularly fortunate as far as preserved cisterns are concerned, since the Albaicin has quite a few of them that have been, restored, cleaned up and revitalised only recently. The association between the public cisterns and mosques was influenced by the need to perform ablutions before going into the mosque as well as to meet the daily needs of the local residents.

When Granada was christianised, the mosques were converted into parish churches, but the cisterns were kept, their usefulness meant they were preserved over such a long period of time better than other works.

The cistern Jerónimo Múzer described in 1492, took up two thirds of the area underneath the small square that stretches out in front of the Lonja and the Royal Chapel; the other third staying under the Lonja itself. Surprisingly, neither the pillars of the Fish Exchange nor the cement of the surrounding buildings has affected the cistern’s structure. It has a capacity of 157 m2 making it the second largest historic cistern in Granada, only behind the Aljibe del Rey (Royal Cistern) with a capacity of 300 m2. It has left its mark on the floor of the fish exchange, near the current entrance door leading inside the Royal Chapel.

This cistern, although hidden, is the only bearing witness to what was the main mosque of Islamic Granada. We come by here each day as a part of our Essential Granada private tour.

Monument to Queen Isabella I of Castile and Christopher Columbus

In the center of the Plaza Isabel la Católica stands the monument to Isabella I of Castile and Christopher Columbus, a work by the renowned sculptor Mariano Benlliure, erected in commemoration of the Fourth Centenary of the Discovery of America. It was initially placed at the entrance of the Salon Promenade, but in 1961 the City Hall agreed to move it to its current location.

The sculpture stands upon a pedestal. On the plinth and friezes are the names of numerous historical characters related to the conquest of Granada and the discovery of America.

On the sides are two bronze reliefs, one depicting a scene of the Granada War, and the other, a royal reception for Columbus. Upon the pedestal, the sculpture, also made of bronze, represents Isabella I of Castile sitting upon a Gothic throne while listening to the future admiral Christopher Columbus, who, standing, presents the map he showed her during the interview they held in the camp that had been set up in Santa Fe during the siege of Granada. The first Columbian expedition was approved there.

This monument is included in the route of our Essential Granada private tour