Visiting the Alhambra and Generalife Gardens

Are you thinking about visiting the Alhambra? Would you like to know what is it, and what can you see in such a special place?

Index

The Alhambra

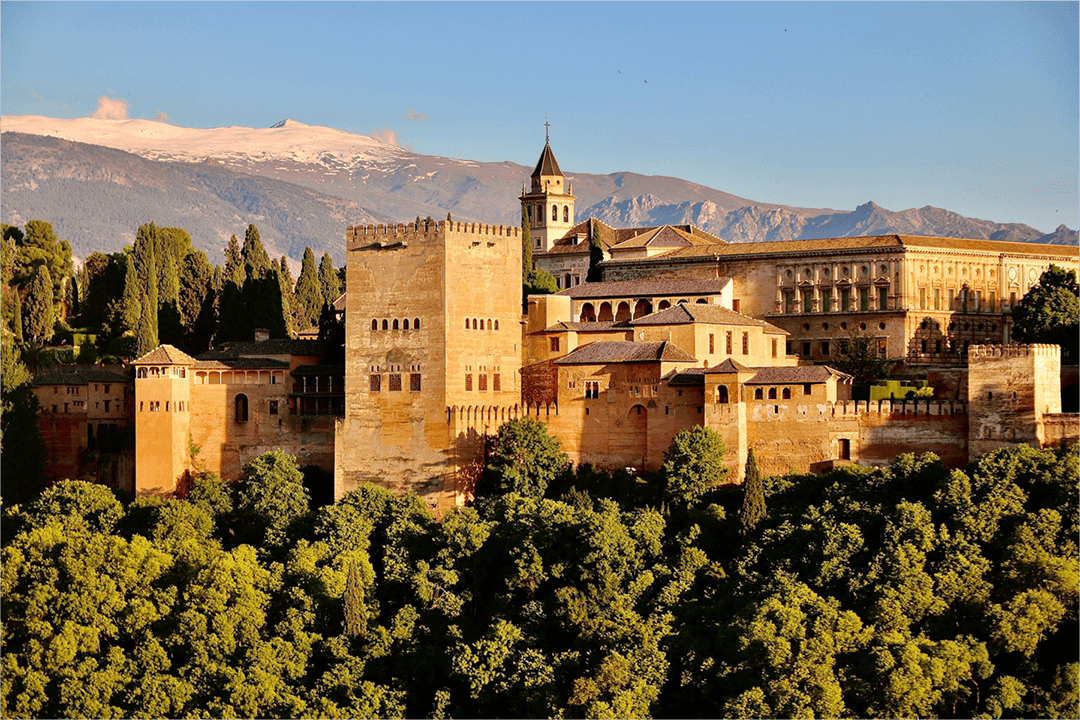

The Alhambra is one of the most beautiful places in Spain, and it’s the soul of Granada. When you are inside it of admiring its view from the many possible viewpoints around the city, it gets perfectly clear why it is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and one of the most famous tourist attractions on Earth.

The Alhambra is a monumental complex full of history and stunning stories, all of which say a lot about the nature of the city of Granada. All the spaces, gardens and palaces have a different story to tell.

The Alhambra was built between 1238 and 1358 at the Sabika hill, it was therefore not built by only one Sultan, it was the work of consecutive rulers of the Nasrid dynasty.

We recommend preparing your trip long before you come to Granada. Follow this link to read on our tips for visiting the Alhambra

Generalife

The Generalife was an almunia, a type of rural Andalusian building (from the Arabic al-munya), which was property of the sultan of Granada during the Nasrid period, with its arable land dedicated to the production of fruits and vegetables, a purpose which has been partially conserved to this day.

There is a stylish palace together with a vegetable garden for the entertainment of Nasrid sultans. It contains two courtyards, the courtyard of the main canal and the soultana’s court. Besides, there are some previous courtyards at the entrance palace. In the exterior zones we can find different garden zones as the high gardens and the lower gardens. Some other singular places are the water stairway and the casa de los amigos.

The word Generalife is the castilianisation of its Arabic name Yinan al-‘Arif, garden of the Alarife (architect). Ibn al-Jatib spoke proudly about the gardens and orchards surrounding the city of Granada and those in it as well, which include the ones of Generalife.

The Generalife is visited in our Alhambra private tour

The Generalife vegetable gardens

The Generalife was the sultan’s closest rural estate to the Alhambra, separated from it by the ravine of the Cuesta de los Chinos, and was a retreat for the sultan when he wished to escape the stresses of ruling.

The successive sultans living in the Alhambra enjoyed the property during the whole period of the Nasrid Kingdom in Granada. After the conquest of the city, the property was handed over to the Catholic Monarchs who placed it under the command of a governor. In the middle of the 16th century, Philip II of Spain ceded it to the Granada-Venegas family, who became the marquis and marquise of Campotéjar, until it was handed over to the state in 1921.

The almunia with its palace and gardens is described by the German traveller Jerónimo Münzer, who came to Granada in 1494 and later again in 1526 by the ambassador Andrea Navagero who visited Granada whilst accompanying the court on the honeymoon of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal.

Casa de los amigos

This house known as the Casa de los amigos (Friend’s house) was the residence for friends and close relatives of the sultan and separated from the Palace of the Generalife but close enough that the guests could have an audience with the sultan.

The preserved archaeological remains of the house with a partial restoration of the ground plan, is what we can see: it is centred by a courtyard with a small pillar attached to a wall and a number of rooms surrounding it.

The toilet is located in the south-east corner and can be seen from above. The southern room, which served as a hall, was the external entrance, with you getting in via a medieval path, a corridor which is still used today.

Courtyards before the palace of Generalife

Before we get to the Palace of Generalife we can find some previous patios. All togegher help us to understand the functions and uses of the Generalife Almunia.

The first courtyard, known as the Patio Polo, is also known as the Patio del Descabalgamiento since it was here where riders dismounted from their horses when they got to the Palacio del Generalife. It was used as a stable, with a drinking trough for the animals and the stables in the lower area as well as rooms (al-gurfa) for the stablemen and hay loft in the upper part.

To get to the Patio Polo in the Nasrid period you followed the traditional path from the Alhambra leading to the Generalife, through the Gate of the Arrabal in the Tower of the Picos and up a winding and steep walled passage. It is at present the first courtyard in the Palace of the Generalife you visit after passing through the New or Lower Gardens.

The next courtyard is known as the Patio de la Soldadesca. Inside the access gate to this courtyard we can see the benches where the guards rested.

Today it is an area decorated with bitter orange trees which provide pleasant shade, a small fountain in the middle and benches where visitors could sit and rest. The crossing to the Patio de la Acequia is done via a steep stairway which shows the two key Nasrid symbols (greeting and domain): the hand and the key inside it.

The water Stairway

The water stairway (escalera del agua) is one of the most unique and special parts of the whole Monumental Complex of the Alhambra and the Generalife: A stairway with water flowing down the banisters. It is a part of the water system of the Alhambra and Generalife since the Acequia del Tercio canal supplies the water stairway. Cicerone has a tour dedicated to discover the ingenious water system built at the Alhambra: The Hydraulic System: Conquering Water at the Alhambra

The water stairway is located above the Patio del Ciprés de la Sultana and it seems that following it you used to arrive at a small chapel we lack archaeological information on. The stairway has three small round pools along it with three small fountains which, as you went up meant you could perform ablutions (al-gude) or ritualistic cleansing prior to prayer. In the area where the chapel is to have been located, the house referred to as the Mirador Romántico was built in the 19th century.

It is definitively one of the few Nasrid elements conserved in their original state in the Generalife, since the water stairway is mentioned in 1494 by Hieronymous Múnzer, in his book “Viaje por España”.

Nasrid Palaces

Probably the most photographed place of the Alhambra, its Palaces, the Nasrid Palaces. Former residence of the emirs of Granada, we offer you now more information about its history and corners before coming to visit them.

At our Alhambra tours page you may find out the different options of guided tours we offer and which ones enter the Nasrid Palaces.

Palace of the Lions

The Palace of the Lions was called “the Garden of the Lord” or Riyad al-sa’id in the Muslim period and was designed around a main central area, that being the courtyard which gives the palace its name. Around this patio there are halls known as the Sala de los Mocarabes, Sala de los Abencerrajes, Sala de los Reyes and Sala de Dos Hermanas.

The Nasrid decoration on this palace reaches unheard of splendour. The lace appearance on the walls, its elegant columns, the exquisite plasterwork on its walls, its colourful tiling, its muqarnas ceiling and its perfect proportions all help create a setting promoting a joyous existence.

Paradise on Earth: Palace of the Lions

It is a symbolic representation of paradise as described in the Christian and Muslim religions, according to which it is symmetrically divided into four parts separated by rivers or canals converging in a central fountain.

Under the overhang there is an endless amount of arches which are held up by 124 columns which follow the proportional layout system starting with the diagonal of a square and reaches the highest degree of perfection. It is interesting for visitors to observe the enormous variety of capitals which can be recognised between the colonnade of the main courtyard.

The longer axis is centred by a main arch which acts as a portico while the minor axis leads into two cube shaped pavilions, covered on the inside with hemispherical domed ceilings, and on the floor there are fonts or recessed fountains.

Even though there are similarities with the Mudejar cloisters, in truth, the main courtyard acts as a connecting and distribution perimeter corridor for the different rooms in the palace as if they were tents surrounding an oasis.

The elimination of the medieval entrance makes it impossible to visit the complex as one was able to in the 14th and 15th centuries. Currently there is an entrance from the Palace of Comares, since in the 16th century the street known as Calle Real Baja was closed in order to make the Charles V Palace, and they were joined from the inside, forming what was dubbed Casa Real Vieja (Old Royal House).

Court of the Lions

The Court of the Lions is the center of the so named Palace. The axis of this palace is different from axis of the Palace of Comares, due to the axis of the previous garden, from the 18th century, upon which the Baths of Comares was designed that has a north-south axis while the Palacio de los Leones has an east-west axis.

This perimeter portico would adhere more to the idea of a Christian cloister than the traditional Nasrid design of a courtyard with porticos on shorter sides, such as the one in the Palacio de Comares.

The original door was found at a south-east angle which provided entry with a diagonal view of the courtyard.

Distribution of the Court of the Lions

The courtyard has rooms on all four sides: on the two shorter ones, to the east and west, there is the Sala de los mocárabes and the Sala de los Reyes, and on the two longer ones, to the north and south, one finds two large residences, the Sala de los Abencerrajes and the Sala de Dos Hermanas.

A portico or gallery completely surrounds the courtyard. It is held up by pillars and arches in a marvellous combination of solids and openings: they are repeated in number and form, placed symmetrically. The gallery’s arches are not load-bearing because the sebka decorating them is hollow as can be noted when the sun shines between them.

On the shorter eastern and western sides, two wonderful pavilions stand out. A wide white border was added below the eaves, where Arabic plasterwork was reused along with the inclusion of the imperial shield.

The courtyard was divided by several platforms into four parterres which created a garden below with orange trees and flowers; the canopies of the orange trees could be reached by hand and the scent of orange blossoms filled the area, forming a cross, with the Fountain of the Lions built in the centre.

Fountain of the Lions

The Fountain of the Lions is the greatest example of Nasrid contributions to Islamic art, showing one of the few known sculptures of animals. It is also, without a doubt, the focal point of the whole palace and aspect that always leaves it mark on visitors.

The twelve lions maintain characteristics which make each of them unique. They are in an alert position, tail down, ears raised, teeth clenched, tensed and awaiting the slightest sign or order from their lord, the sultan.

On the other hand, the association with purifying water, fountain of life, and the image of the lion, guardian of power was lost during the beginnings of humanity, but is integrated symbolically into the traditions of the great monotheist religions.

The Fountain of the Lions is comprised of a central bowl held up by twelve lion fountain spouts, done in white marble from the quarries of Macael, in the province of Almeria. On the edge of the fountain there is a poetic inscription by Ibn Zamrak eulogising Muhammad V, the sultan under whose reign the Palace of the Lions was built.

Due to multiple factors: extreme climate conditions, low water quality, human activity and chemical reactions on the surface of the stone, both the lions and the cup have suffered over the course of history, and a lot more in recent decades, which have progressively changed the formal and aesthetic aspects of these pieces of art, which made restoration work by the Patronato de la Alhambra necessary.

Restoration of the Fountain of the Lions

After eight years of restoration, in 2012 the lions were returned to the fountain lustrous in their original while colour. Furthermore, as a consequence of the research carried out during the restoration process, a sophisticated and modern enclosed 5000 litre hydraulic water system allowing the pressure, temperature and level of the chemical products to be adjusted for all of the hydraulic parts of the Palacio de Leones was installed: Fountain, lion-spouts, canals and fountains of galleries and of the main halls: Sala de los Abencerrajes and the Sala de Dos Hermanas.

Researchers have also determined that the complex must have had marble floors, which is confirmed by numerous witness accounts from the time, such as the one by the historian Jerónimo Münzer, and the ambassador Andrea Navaggiero. For them, the courtyard was made from white marble and the crossing of the canals coming from the fountain symbolised the four rivers leading to paradise. Seven centuries later, Macael is still the quarry providing the material for the Alhambra’s architects. The new flooring allows more uniformity and harmony in the Patio, prevalent today in white compared to the grey tones of the past. 250 pieces of this material have been installed.

Mirador de Lindaraja

You could say that the Mirador de Lindaraja is one of the most beautiful corners of the Alhambra.

The name seems to have come from the phonetic corruptions of three words in Arabic: “ain-dar-Aixa” (the eyes of the House of Aixa), from which only the landscape of the Albayzin could be seen due to there only being a lower garden where the Patio de Lindaraja now lies.

It is an excellent example of the palatial ornamental architecture of sultan Muhammad V, with twin, cambered and engrailed arches, through which you were able to look out on the city of Granada, before Emperor Charles V’s renovations.

Its interior contains the most exquisite decorations in the whole palace, with geometric and epigraphic compositions and very delicate plasterwork which frames the front window, below a blind arch of muqarnas.

The bases of the tiny tiles show a succession of star wheels, finished with inscriptions using characters formed from pieces of black ceramic on a white background in the style of a puzzle.

Lightning of Daraxa

The lookout is covered with ceiling employing assembled coloured glass in a wooden vaulted structure using a roof lantern.

The lookout, which maintains the original height of the window sills, is covered by a wooden trough with the original glass from the Nasrid period; One is the light, but the colour varies” one can read on the lookout’s poem.

On his honey moon in 1526, Charles V used this hall as a magnificent dining room.

Starting in 1528 a residence was built for the emperor around the lower garden, which moved it closer to a cloister shape and modified its original appearance.

Palace of Comares

Patio de Comares

Through the door to the left of the Fachade of Comares there is a double door with a bend giving way to the heart of the palace: the Patio de Comares or the Patio de Arrayanes.

The Courtyard was an orchard-garden planted with low lying fruit and aromatic trees, such as pomegranate and orange trees, and myrtles.

The large water tank is a mirror, like a glass floor where the architecture of both the southern nave and the tower of Comares are reflected.

On the longer sides of the patio there are the residencies of the four legitimate women of the sultan, comprised of lower and upper floors which are not connected on the inside; one must go out to the courtyard in order to go up the appropriate stairs which lead to the small doors.

Distribution of the rooms of the Patio de Comares

The ground floor was used more in summer and the upper floor in winter. The lower rooms, which are accessed through a wide arch with niches or small openings in the walls, which are lengthened with bedrooms on both sides, marked by a small step and an arch above, and cupboards built into the wall. The natural light came in in through the latticework windows which are on the entry arch, which also provided airflow and kept the rooms cooler inside. These are the typical female lodgings where daily private and family life occurred. On the flooring of the bedrooms there is a wooden structure to insulate the bed, and cushions and rich fabrics were placed on it. Cooking was done on clay stoves, and heating was done using ceramic and stone braziers. Artificial lighting was supplied by elegant clay or bronze oil lamps.

The southern nave is made up of three floors: a portico with columns which hold up seven arches and a back room, two intermediate rooms with latticework and above there is a small portico and another back room. This was the area where the Arab and Christian palaces came together, and in order to build the latter one the back rooms had to be partially demolished. This is the only part lacking due to the construction of the Palacio de Carlos V in the 16th century. The sons of the sultan lived in these lodgings along with their teachers; they were separate from the sultan’s lodgings yet controlled by him.

This main area was the focus of the architects involved in conservation efforts: José Contreras from 1841-1842, Juan Pugnaire in 1872, Mariano Contreras in 1899 and 1901 and Leopoldo Torres Balbás between 1925 and 1936.

Salon del Trono

The Salón del Trono or Sala de Embajadores is the most gradiose qubba or room to be found in the palaces of the Alhambra’s medina, and is designed as a tower-palace.

It is the private hall of the sultan (maylis jass). Its layout is square and has nine bedrooms surrounding it. It is 18 metres high.

In this hall the sultan held splendid receptions setting himself up in central Northern bedroom and the guests, members of the court, and key Nasrid families in the rest of them. The hall would have been lit with beautiful lamps including oil lamps, and heated in winter with warming pans.

Salon del Trono: Heaven on earth

During Muslim times all of the openings were covered with leaded glass, decorated with geometric motifs, which offered protection against the bitter winter cold, as well as wooden lattices which avoided the blinding light of Granada summer. This technique, called Comaría, gives the hall its name and hence the whole palace as well.

The rich decoration of the hall is extraordinary: there is not a single part which is not decorated with floral (arabesque), geometric or epigraphical themes, from the ceiling to the floor and done with a diverse range of materials, such as ceramics, stucco and wood. The floor was ceramic- wonderful tile and lattice work decorate its bases- with the walls covered in stucco which maintain some of their original colouring. In the tile-work on the bases, the Arabic artists experimented with diverse geometric designs which they later applied to the ceiling.

The ceiling is a great wooden dome, made up of more than 11000 pieces, which represent Islamic Paradise through geometric shapes: According to the Koran, paradise is made up of seven overlapping heavens and reaches its peak with the eighth heaven topped with the Throne of Allah, which in this dome is represented by a red shell, since red was the colour of the Nasrid flag.

The Throne room is the symbolic representation of Paradise, topped by the transcendence of Allah, who legitimises the power of the sultan on earth with his immanence. On the framework the whole Sura or chapter, LXVII called al-Milk (Kingdom or Lordship) was carved, spreading out its 30 verses on the four sides.

Fachade of Comares

Across from the portico of the Cuarto Dorado one finds the most important façade in the palace: the imposing Fachada of Comares. It was built by Muhammad V to commemorate taking Algeciras in 1369.

The sultan received the subjects who managed to get a special audience with him.

On the central part of the façade, between the two doors, the sultan sat on a Savonarola chair below the great overhang which was the canopy serving as his crown, as the inscription says; an overhang which is only one of the masterpieces of Nasrid carpentry. That is how the theatrical effect was prepared prior to the monarch’s arrival. Meanwhile the women discretely observed the whole ceremony behind the latticework of the windows on the upper floors.

It is found on three steps of stairs in while marble, and its arabesque decoration is in increasing order from the bottom-up.

The door to the right was used as an entrance to the service area and the one to the left for the Patio de Comares.

Bath of Comares

On the north-east corner of the courtyard there are two doors which lead to the Bath of Comares of the Palace of Comares.

In addition to its traditional purpose it had another more specific purpose, directly related to politics and diplomacy. The location of the door, close to the Chamber of the Ambassadors, hints at it. For those reasons it was used especially when the friendship and favour of diplomats and politicians from other kingdoms needed to be won over.

The upper part, at the level of the Comares courtyard, is made up of the room known as the Sala de Desvestirse (changing room) or al-bayt al-maslaj with a small bathroom, and the gallery looking out on the lower part.

The lower part of al-bayt al-maslaj is called the Room of the Beds or the Room of Rest, because there are two large stonework benches, with cushions, for resting in lively conversation before and after bathing. In the centre of the room there is a low fountain and the marvellous tiling covering its floor.

Bath of Comares distribution and uses of the rooms

From there one enters the al-bayt al-barid or cold room, with two lateral bedrooms and in one of them there is a cold water font and in the other the al-bayt al-wastani or lukewarm room. The floor of the bath, with the exception of the first room, was made of marble, and it was covered with vaults and skylights (madawi) which offered lighting from above. Separating or moving the glass closer to the skylights enabled the amount of steam to be regulated. There is an open font in a small arch on the wall which poured hot water onto the floor and as it evaporated steam was produced. The glass of the skylights was red and white coloured.

The hot room or al-bayt al-sajun has two large immersion fonts for hot water. On the large immersion font there is a little decorative marble arch on which a poem by Ibn al-Yayyab in honour of Yusuf I is written.

The servicing area for this bath had a boiler used for heating water, and the oven (al-furn) with its hypocausis held up by brick pillars which open up in the shape of a palm tree to support the upper floor. The one that produced heat, and as previously mentioned the correct amount of water produced steam.

In this bathhouse you can also note that hammans do not only have a hygienic purpose, but also have a social funciton one.

In the Bath of Comares we can observe how the idea of pleasure and hedonism was as important in Islamic life is felt. Conversation was enjoyed alongside the contrast between two opposites: the cold and heat.

Rafael Contreras who restored all of the plasterwork while Mariano Contreras, Modesto Cendoya, Leopoldo Balbás and Pedro Salmerón gave it colour. It can be visited when it is available in “Area of the month” promgram, regulated by the Patronato de la Alhambra who is in chrage of the vistis and conservation of the monument.

Palacio del Mexuar

History of the Nasrid Palaces

Isma’il (1314-1325) built the area of the Mexuar, and his son Yusuf I (1333-1354) defined the overall structure of the palace (The patio del Cuarto Dorado, the Court of the Myrtles, the Royal Baths and the Patio de la Reja). However, his sudden tragic death, being assassinated by a slave while in the great mosque during Friday prayer, meant his son Muhammad V (1354-1359/1362-1391), was to finish construction of the palace, during his first reign.

The Court of the Myrtles was fully independent from the Court of Lions in the medieval period. But the new Christian mindset resulted in them being combined to conform, in the time of the Catholic Monarchs, to what we refer to from then on as the Royal House. The Count of Tendilla carried out renovations in 1492 and years later further ones to adapt the Arabic palaces for Christian needs. In 1526, for Charles V and Isabella de Portugal’s honey moon, there was more work done, which continued on throughout the 16th century

In the 19th century, after the disaster brought on by the French when leaving the Alhambra, between 1810 and 1812, Fernando VII named José Contreras as head architect in charge of preservation in 1828.

The abandoned state was in during the 18th century. The damage from the war is reflected in the art by travellers such as Richard Ford, Girault Prangey and David Roberts. From 1851 to 1884 Rafael Contreras carried out projects and work in the Court of the Myrtles and the Court of Lions. His son, Mariano Contreras, did the same after him, from 1890 to 1905.

Alcazaba, the fortress

This great fortress located in the Nasrid medina was first built as a small alcazaba (fortress) in the period of the Taifa kingdoms (11th century), in the Ziri period, and was preserved during the Nasrid period reforms (13th to 15th century).

It is the silent embryo of an entire aristocratic city which would later be called Madina al-Hamra (city of the Alhambra) and was unjustly forgotten by those who wrote about the Nasarid Palaces after the Conquest.

This alcazaba is on the western end of the Sabika hill. It is triangularly shaped and is built with rammed earth walls and towers. It was the main defence against attacks.

It is the oldest part of the complex and this was where the red castle was originally located. Muhammad I built the walls and the three towers: Torre de la Vela, Torre Quebrada and Torre del Homenaje. Later on an additional tower was built: Torre de la Pólvora

The soldiers responsible for defending the Sultan and the Alhambra lived in the Alcazaba. A path goes through the middle of the Alcazaba and the smallest houses were designated for single soldiers without a family (to the left) while the larger houses where for the soldiers and their families (to the right).

There would have been an arsenal, silo and a bread-making oven for preparing food.

After the Expulsion, it was adapted to modern military defence and attack techniques with additional towers being built: Torre del Cubo.

Jardín de los Adarves

The garden has this name because of its location on the lower walkway of the fortress. It is a deep pit which separated the inside of the complex from the exterior.

At the start of the 17th century (Renaissance period) the Marquis of Mondéjar ordered it filled in to make a garden, organised with two Renaissance pillars and vegetation on the inside.

Today it is one of the places for enjoying one of the city’s most beautiful landscapes. On the western side of it there is a lookout point where the wall connecting to Vermillion Towers begins.

Military Quarter

Inside the Plaza de Armas (Arms Square) there was a camp with campaign tents for the military garrison, with a large aljibe (cistern) built for it with two naves, in a south west angle ensuring the water supply.

The old military camp became a stable with small brick homes, some with multiple stories and organised around the main street; silos and wells were also opened.

The casa principal (main house) is located between the homes. It belonged to Muhammad I and afterwards, to the military commander.

It is much larger than the rest, with an entranceway, lavatory, courtyard with pool, and side bedrooms with built-in beds. There was also a small private bathroom. There was a street behind it, backing on to the wall, in order to be able to flee in case of emergency to the Torre del Homenaje (Tribute Tower).

Torre del cubo

Connected to the outer wall of the Torre del Homenaje, this semi-circular tower was built after Reconquest around 1586 on an Islamic door.

Its name comes from the fact that the magazine is located at the end of the street which went along the whole Secano, and today is a terrace from which you can look out at the beautiful views of the Albayzin and the Darro valley.

It was a small military tower located in the south-east corner of the Secano which acted as a buffer for the impact from cannon balls that were commonly used. It is connected to the wall which joins the Alcazaba to the palaces.

Tower of Arms

The tower known as the Tower of Arms or Torre de Armas was built by Muhammad I, Ibn al-Ahmar (1238-1272). It is a complex structure with an entrance way, a twist, straight stretch and two exits: one to the east which was the entrance for citizens, and that would have gone via the barbican ditch to the Tahona Gate and the Urban Organization Square, and the other to the west, only for soldiers leading to the stables.

It is one of the most complex gates in the whole Alhambra, and was the main entrance to the Alcazaba for citizens who came up from the Albayzin. It was called Torre de las Armas, Tower of Arms, because this was where those entering the Alhambra had to leave any arms or weapons. It also has an upper floor for guards and a terrace.

Midway through the 16th century this gate stopped being used as the main entrance to the Alhambra, when the Puerta de los Carros was opened converting the Justice Gate, (Puerta de la Justicia) or Esplanade, on the southern part, into the main entrance for citizens.

Vela Tower

Vela Tower was built by the founder of the dynasty, Muhammad ben Nasr (1238-1273) as a feudal style residency tower. It is extremely difficult to enter and became an almost unassailable entrance. It is also known as the Watch Tower, and is the Alhambra’s most symbolic tower.

The tower has lost some of its original height due to losing its battlements in the catastrophes which have occurred since the 16th century: an earthquake in 1522, the explosion of the powder keg in the Darro valley in 1590 which left it breached and lightning in the 19th century that destroyed the bell bulbrush.

It has four floors plus the terrace: a subterranean dungeon with silo and three floors. It is the most important and most western tower of the Alcazaba meaning it also serves as a vantage point for the Albayzin, the medina and the whole Vega of Granada. After the Christian conquest the four floors underwent modifications and were turned into residences, which is why their appearance has changed compared to how there were originally.

The tower was finished off with a bell, which the Christians installed after taking over the city and which was used to regulate irrigation shifts in the Vega and to call residents on tragic occasions such as the 1890 fire. It is said that the tower is called “De vela” (staying awake) because ringing the bell meant keeping everyone up.

Every 2 January the Torre de la Vela and its bell take on an important role once again. As a part of the commemoration of the Taking of Granada, there is a tradition where young single women in the city who ring the bell on January 2nd will get married before the end of the year.

Partal

In Arabic, Bartal means “arcade”, but today we use Partal to refer to the area of the Alhambra where the first palaces in the Medina de la Alhambra were built.

Made up of small terraces, they are stepped beds that form “hanging” gardens, which are adapted to the uneven terrain.

All of these gardens are located on the archaeological remains of houses and palaces, which, for the most part, have only preserved the central pools. The gardens surrounding these pools protect the important archaeological remains until the archaeological work, which began at the turn of the 20th century, is resumed.

Partal Gardens

From 1924 onwards, Leopoldo Torres Balbás designed the gardens known as Partal Gardens in the French style; with hedges, keeping the garden beds and recreating the architectonic spaces, such as the pavilions and arcades of the palace that no longer existed.

In addition to being home to some of the most welcoming gardens in the entire Alhambra, El Partal also includes the palaces known as Palacio Partal Alto and Palacio Partal Bajo, along with the small adjacent houses, and a small mosque.

Tower Promenade

Next to the wall that defended the real citadel of the Alhambra a series of defensive towers was built. They served at the same time like dwellings, joining the Partal with the Generalife. This nice walk is nowadays known as the Promenade of the Towers.

Free Access Urban Zones

Aljama Mosque

The Aljama Mosque (great mosque) of the Alhambra was built by Muhammad III in the first year of his reign, 1303.

The haram (prayer hall) had three naves held up by pillars and an octagonal mihrab facing Mecca. It was richly decorated by the sultan with a mimbar for leading prayer and beautiful metallic oil lamps, one of which is preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid (a repllica can be seen inside the museum of the Alhambra). Part of the floor of the mosque, which remains outside the church to the south, was excavated by Modesto Cendoya in 1922.

In this mosque the sultan would lead mass prayer on Fridays and a cadí would give his jutba (sermon) in the Malakí orthodoxy prevailing in al-Andalus in the 8th century. In 1304 a mimbar inlaid with precious stones was added, with the intention of making it even better than the one put by the Ziri Badis in the 11th century in the great mosque of Granada, which was located where the Church Sagrario de la Catedral in Granada would later be erected in the 18th century.

In al-Andalus the religious domain loyal to the Sunni orthodoxy was followed, and within the sunna (tradition “the ways of the ancestors”). Mystic Sufi music was also introduced to our lands which spread across the whole Islamic empire. In Nasrid Granada there were renowned sufis such as Ibn al-Jatib.

Next to the fountains or mida in the courtyards of the mosques the compulsory ritualistic cleansing was performed. This obligation was so strict that even if there was not any water, it had to be done with clean sand, a rite known in Arab as tayammum. The Koran fully explains how it must be performed.

Yusuf I was murdered in this mosque when praying on the day of the Breaking of the Fast (Fitr). He was killed by a slave consumed by madness, but there is no doubt that there was someone else behind the palatial intrigue that was so common in the Nasrid court.

In order to maintain the mosque, Muhammad III ordered a hamman or bathhouse to be built as well as an adjacent palace. With the profit earned from the bathhouse, part of the expenses of the mosque was covered as was customary in the Islamic world.

From the arrival of the Catholic Monarchs, the Mosque became a Church consecrated to the Virgin. The Muslim building was demolished and built the current Christian temple with invocation to Santa Maria de la Alhambra.

Church of Santa María de la Alhambra

In 1492 the mosque was converted into a church, the Church of Santa María de la Alhambra, being dedicated to St. Mary, as was decided by the Catholic Monarchs. Later on, the mosque would be extended, with a chancel added at the base. The first seat of the archbishop was set up there. Later on, the decision was made to build a church and the old mosque was demolished.

The Iglesia de Santa María de la Alhambra was built starting in 1576 and was finished with designs by Ambrosio de Vicó in 1607. Previous plans had been drawn up by the royal architects Juan de Herrera, the builder of El Escorial, Juan de Orea and Franciso de Mora, which had been rejected due to their high financial cost and their style which did not fit in with our land’s prevailing Mudejar style.

Its structure is simple, with a single nave of three side chapels in each one, a wide transept covered with a dome and side tower. The exterior was done following the Mudejar tradition, with brick, except for the base which was made of stone. Unfortunately no façades were made, neither the main one at the base, nor the one at the side, remaining undecorated, featuring only the royal and episcopal crests on the main façade, and the tower’s steeple.

Interiors of Santa María de la Alhambra

The interior features a reredos dominated by a Crucified Christ by Alonso de Mena, with Saint Ursula and Saint Susanna beside him, also by Mena, and rounding off the Trinity. La Piedad by Torcuato Ruíz del Peral is also in a chapel which is featured in the procession of the Hermandad (Brotherhood) in Santa María de la Alhambra. This popular virgin is worshipped by many Granada residents and is on display in religious processions through the streets of Granada on Holy Saturday.

In the 19th century the Visigoth inscription by noble Gudiliuva was on the door of the Sacristy, and it is now in the Museum of the Alhambra. Three churches were built in Granada in the Visigoth period and the church San Esteban may occupy the same plot of land as the mosque and later churches, although we do not have the archaeological evidence to confirm it.

In the small square at the foot of the church a cross was raised by Don Pedro de Castro with an inscription in Latin and Spanish where the martyrdom of Franciscan friars Juan de Cetina and Pedro de Dueñas in the Alhambra in 1397 is described.

Cistern Square, Plaza de los Aljibes

In the Muslim period this area between the Alcazaba and the palace area was taken up by a large square and a drop off with a tower.

It is the space where the whole urban structure of the Alhambra was organised; here is network that was used to organise the medina. From the square you could choose which path you wished to take: enter the palace of Comares via the first courtyard, the palace of La Madraza de los Príncipes, or go via the ramparts of the lower wall to the Palace of Comares, in a subterranean passage, until the tower of the Peinador de la Reina in the Palacio de los Leones, or finally go up, after passing through another gate via Calle Real to the Puerta del Vino to enter the medina.

A rectangular great aljibe (cistern) with two naves was built into area beside the drop between 1492 and 1494 by the count of Tendilla, so the Alhambra could withstand a hypothetical siege of the large and majority Arabic Granada population in the Medina and the Albaycin. That is why today it is called the Plaza de los Aljibes (Square of the Cisterns).

Each nave was covered with a vault, measuring 34 metres long, 6 metres wide and 8 metres high. The cistern has eight access points but with only one of them is open where the famous well of the cistern of the Alhambra is, where the water carriers went as told by Washington Irving in his “Tales of the Alhambra”.

First Cante Jondo Competition

In 1922, at the Cistern Square, the first “Cante Jondo Competition” took place, organised by Granada intellectuals, among them the poet Federico García Lorca and the music composer Manuel de Falla, as recalled on the plaque placed there in 1976 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the festival.

In the period of French domination, between 1810 and 1812 a new route to the Alcazaba was created for artillery on the southern wall. A commemorative plaque was placed on this route recalling the feat of the spanish soldier José García, a disabled corporal, who, by putting his own life at risk, saved a part of the southern wall, the Puerta de la Justicia, the Alcazaba and the Alcázares from the blasts ordered by the French General Sebastiani when he withdrew from the Alhambra. Unfortunately the whole southern part was blown up, from Torre del Agua until Torre del Palacio de Los Abencerrajes.

Gate of Wine

The Gate of wine (Puerta del Vino) was built by Muhammad III as a commemorative symbol of royal power and later on it was redecorated by Muhammad V

This door allowed access to the upper Alhambra and it is where the street Calle Real started, hub of the medina; it was also used as an intersection and border between the military and civil areas.

It was called the gate of wine because in the Christian period in the 16th century taxes had to be paid on wine entering via the gate that was destined for the Alhambra, giving rise to a wine market which would occur inside starting in 1554.

Gate of wine façades

The eastern façade is the most interesting and elaborate since it has some beautiful tiles in the haimet and above there is another double window (double arched).

Its western façade stands out for its arabesque decoration and flower cut into stone, with a double window. It is the oldest and coarsest, showing one of the few horseshoe pointed arches and the symbolic key.

Beside the western façade there is a small plaque with the following: “To Claude Debussy for The Puerta del Vino” remembering the composition by the French musical genius in one of his Preludes for piano: “La Puerta del Vino”.

Inside we can see the framework on the wooden doors and the benches for the guards to rest.

Nasrid House of the Calle Real Street

This Nasrid house was built by Muhammad III in 1304, according to Ibn al-Yayyab, and follows typical Nasrid design with a courtyard containing a pond and surrounding rooms, of which only two survive today: one on the western wall and the other on the southern side. From the northern room only the wall remains with its plaster arches and Arabic plaster decoration. The eastern room is missing since it was eliminated to expand the Placeta del Guindo.

Ibn al Yayyad celebrated the construction of the palace in a beautiful poem in his Diwan:

“You have built a residence in front of the blessed mosque

Because in it lives the blessed one;

It is like a fiancée who appears on her seat of honour

And because of her, the gaze scorns the gaze of the young virgins;

Their eyes remain prisoners and the gazes

Cannot move nor can they stay still:

The adornments of the beautiful women

They cannot overtake the beauty of your art; it is like a garden where the rain

Has embroidered images with marvellous brocades and colours;

She shows the men her charm, and would you believe that

There are tunics embroidered with flowers from the garden;

The earth has bestowed her beauty upon her

Which has centuplicated;

The noble dome on the outside shining

Like a clear and gorgeous beacon”

The Nasrid house can be visited as a part of the programme “Space of the Month”.

Palace of Charles V

It takes up part of the sari’a and is the high water mark for imperial architectural statements designed by the marquises of Mondéjar. There were orders to build and equip the rooms in the Arabic palaces for Charles V and his wife Isabella of Portugal, for their honeymoon in 1526, since the existing ones were not to the Emperor´s liking, nor were they big enough for the court.

Pedro Machuca, a squire of the Counts of Tendilla, was in charge of the project and also designed the Puerta de las Granadas and the Pilar de Carlos V for it.

The foundations were started and the four façades were completed between 1527 and 1537, and from that year to 1550 they worked on the main façades, the western and southern ones, and the patio that is covered with an annular vault. When Pedro Machuca died in 1550, he was replaced by his son Luis, who continued construction as according to his father’s design. Work came to a halt upon the death of Luis Machuca, starting again in 1572, by order of Philip II.

In the 17th century, little work was done due to discrepancies between the projects, but primarily because of the limited funds allocated to our palace. However, the palace remained unfinished, since they had built the façades, both floors of the circular courtyard, the crypt and the chapel, but the mezzanine and the upper roof were still missing.

From 1923 to 1935 the palace was finished following the orders of Leopoldo Torres Balbás. He used the old ashlars buried in the Secano, did the mezzanine and completed the upper rooms, and covered the whole palace with a rooftop terrace. In 1957 the Museo de Bellas Artes was moved into the upper floor. In 1968 Francisco Prieto-Moreno Pardo covered the high gallery with a roof.

Place of Charles V Façades

The western entrance was done between 1551 and 1563 in grey stone from Sierra Elvira with a large door that was finished with winged victories. The lateral pedestals are symmetrical, representing war scenes, with soldiers and arms. The central pedestal represents the triumph of peace, symbolized by two women sitting on the arms which are burning two spirits. The women are between the Pillars of Hercules and they are accompanied by the globe of the world with the imperial crown. There are medallions on the falcons in white marble where Hercules is represented killing the lion of Nemea, in the middle of the Spanish Coat of Arms, and Hercules with the Cretan Bull.

The southern door was done between 1536 and 1554 and is also made of grey stone from Sierra Elvira. The lower part has four pillars from the Ionic order, finished with an entablature with the inscription: “Imp.Caes.Kar.V.P.V.” (Emperor and Caesar Charles V. Plus Ultra).

The iconology on these façades praises the victories of Charles V: on the western one, the land victory in the battle of Pavia over Francis I of France, and on southern one, the sea victory in the battle of Tunis over Berber pirates.

On the northern side there is a small façade with the inscription “Imp.Caes.Karolo V”

Placed up high in the circular courtyard that surrounds the lower gallery made with large Tuscan Order pillars with stone from Turro (Loja), while higher up the gallery has Corinthian order pillars.

The Renaissance and Arabic palaces are so integrated that only the large façades on the western and southern sides are worked, and it is also on these façades where the rings are found for tying horses above the continuous bench for mounting and dismounting. The rings have an eagle in the corners, and lions on the rest of the façade.

We know that the Arabic residence was destroyed while only part of the Sala de las Helias in the courtyard of Comares and part of the Rauda Real were destroyed.

The street named Calle Real Baja was permanently cut off, and Calle Real Alta had its route modified. You can see its remains in one of the rooms in the Museo de la Alhambra.

Two museums are located in the Palace of Charles V: the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo de la Alhambra.

Polinario Baths

Polinario Baths are also known as Calle Real Baths or Mosque Baths. They were a tavern in the 19th century and received the intellectuals of the day. The great classical guitarist Ángel Barrios was born there. In modern times a Museum-House dedicated to him was built connected to the bathhouse. The bath was re-established by Leopoldo Torres Balbás between 1935 and 1936.

The entrance is in the street called Calle Real Alta (High Royal Street), between the bath and the adjoining palace, via a passage way providing access to the al-bayt al-maslaj (relaxation room), which has a beautiful lantern and leisure beds, similar to the later-built Comares Palace. From there you can go into the al-bayt al-barid (cold room) and al-bayt al-wastaní (temperate room) which has two immersion pools.

Today, the al-bayt al-sajun (hot room) only maintains the immersion pool and the boiler from which we can see the columns of the hypocausis that held up the room.

Public Baths or Hammamats

The use of public baths was fully controlled as far as gender division was concerned; in the morning for men and in the afternoon for women. The tayyab (workers) were in charge of its operation and cleaning, while the hakkak (masseuses) worked to relax tired muscles. These hammamat did not only play a role in hygiene, but also an important role in social relations in so far as conversations in the al-bay al-maslaj (dressing room), behind the bath, and a religious one as well when performing the alguado or ritualistic cleansing.

The alguado requirement was more involved at special times of year such as the great Feast of the Break of the Fast at the end of Ramadan, or id al-fitr, when a full cleansing of the body was done, and which had to take place in a bath.

Alhambra surroundings

Alhambra forest

Behind the Puerta de las Granadas (Pomegranates Gate) are Las Alamedas, the Alhambra forest, which are found on the edge of the Alhambra starting at the gate and continue until the Torre del Agua (The Tower of Water), including the new walkways, Torres Bermejas (Vermillion Tower) and hill up to the Generalife.

They were not designed until the 17th century and it was in 1729 when they were created with three walkways as a part of the preparations for Philip V’s visit in 1730. The three walkways were adjusted for the arrival of Infante Don Francisco de Borja Borbón and his wife, lowering the main walkway to make it easier for carriages to go up.

The great cemetery of the Sabika, the Maqbarat al-Sabika was in this area in Muslim times, although there is no archaeological evidence regarding its location. It was in this cemetery where they buried the first Nazari Sultan, Ibn al-Ahmar or Muhammed I and Sultans Muhammad III and Nasr, as well as Yusuf I’shayib or general in chief Ridwan and other Medina courtiers over the Nasrid period.

The majority of the trees are poplars, blackberries and elms.

A walk thorugh the Alhambra Forest

The walkway on the left-hand side, Norte, is pedestrian only and begins at a marble cross paid for by Leandro de Palencia, artilleryman for the Alhambra. This cross was toppled one night in 1932 and erected again by Leopoldo Torrés Balbás. The walkway heads up through the woods until reaching the Pilar de Carlos V (Charles V’s Pillar) and the Justice Gate or the Explanada.

The walkway on the right, Sur, is also pedestrian and goes up through the woods until Campo de los Mártires and via a side walkway goes to Torres Bermejas. At the start of this walkway, just beside the Puerta de las Granadas, there is a stone with a panegyric to al-Ahmar, the founder of the Nasrid dynasty. A large dungeon was discovered in Campo de los Mártires in 1928 with served as a jail in Muslim times. It was re-excavated and studied in 1990.

The central walkway or carriage walkway is divided into three stretches leaving you at the place where you can go up to the Generalife from where the Hotel Washington Irving is; the first part starts from a small Renaissance pillar built in 1938, the second part, after the first small square, has us pass by the Arco de las orejas (Arch of the ears) built in 1933 to save what was left of the bab al-Rambla, the Puerta del Arenal, which was located at the entrance to Plaza Bibrambla and was demolished between 1873 and 1884 by City Hall. The Ángel Ganivet Monument was placed along the third part as well as a lean cross a little higher up, done in 1641.

Charles V fountain

The Charles V fountain, Pilar de Carlos V, is a structure that reflects the conqueror’s desire to Christianise the Nasrid city emphasising its importance as an imperial city. It was designed by Pedro Machuca on the orders of Luis Hurtado de Mendoza, third count of Tendilla and the second marquis of Mondéjar, and it was built in 1545 under the mandate of the third marquis of Mondejar, Iñigo Hurtado de Mendoza.

The fountain rests on a large five-section wall divided by Renaissance pillars, three of which take up the frontispiece of the great pillar.

Charles V fountain sections

The first section with three nozzles or pipes carved with human heads representing Granada’s the three rivers: Genil, Darro and Beiro; although there are those who say that these represent the seasons symbolised by the decorative vegetation: the ears of Summer, flowers of Spring and grapes of Autumn which are baroque additions. At the sides the coat of arms of the House of Mendonza is featured.

The second section is centred by a cartouche where one can read in Latin “Imperatori Caesari Carolo Quinto Hispaniarum regi” (Emperor and Caesar Charles V, king of the Spanish).

A curved pediment rounds off the frontispiece with the imperial crest.

Justice Gate

The Justice Gate is also known as the Puerta de la Explanada or bab al-Sari’a. It bears its name in reference to the esplanade that existed in front of it before the walkways of Las Alamedas were made. It was protected on the left-hand side midway through the 16th century by a square artillery magazine.

A commemorative plaque was put on it in the 20th century recalling that the Alhambra being named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984: “The UNESCO World Heritage Site Committee has declared the Alhambra and Generalife as WORLD HERITAGE sites in the session on 2 November 1984.”

The Justice gate or Puerta de la Justicia is a masterpiece of military engineering that stands out due to its bold solidity and impressive grandeur contrasted against the fragility of the Casa Real

It is the main entrance for the southern wall, built by Yusuf I in 1348 inside the imposing tower. It was always one of the main access points to the Alhambra complex and is characterised by having been the only entrance to the walled area of Madina Al-Hamra.

The exterior is made up of a large pointed horseshoe arch, with the hand of Fatima on the keystone, which conceals an arch of the same design yet smaller in the entrance on the inside of the door, whose keystone is the key which is symbolic of the power and property of Nasrid sultans.

Inside the Justice Gate

The inside of Puerta de la JusticiaOn the capitals of the small arch there is an inscription in italics between the one that cites the sahada or profession of the Islamic faith: “There is no god except Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah. There is no power or force which is not in Allah”

On the inner arch the Catholic Monarchs placed an image of the Virgin and the Child in the middle of a large panel of glazed tiles.

The Justice Gate has a very sophisticated defensive strategy: The first thing to be noted is the inclination of the path leading up to it which is quite steep and would have prevented enemies from arriving quickly and feeling rested. Secondly, now at the door, between both arches there is a space open to the sky to protect the gate using the terrace above by throwing stones and boiling water down from it. Finally, the gate has a double twist that means enemies also are unable to enter quickly. Inside we can see the arches with their benches for the guards to rest, and a wooden structure where the high lances were stored.

The inner arch provides access to the medina, the pointed horseshoe has beautiful cuerda seca (dry cord) coloured tilework, with a design weave. After the taking of Granada a chapel with a reredos was made in this space.

The Justice Gate, rectangular shaped, is connected on one of its sides to the wall of the aristocratic city and was the Alhambra’s most important gate from the 16th century on

Pomegranates Gate

Pomegranates Gate, or Puerta de las Granadas, is the most popular and beautiful historic gate for entering the Nasrid palace grounds of the Alhambra through the Woods of the Alhambra.

Luis Hurtado de Mendoza, third count of Tendilla and the second marquis of Mondéjar ordered the construction of this grand gate around 1536, which was carried out in the 16th century by Pedro Machuca and built on padded ashlars.

Known as the Puerta de las Granadas, it gets its name from the three pomegranates that are open and decorate the triangular pediment that crowns the main arch accompanying the imperial shield, along with the allegoric figures of Peace and Abundance.

This Renaissance gate was built replacing the original Islamic one, the Bib al-Buxar or Gate of the New Joys, also known as Bib al Jadaq or From the Trench, which was a defensive tower protecting the valley between the hill of the Sabika and Monte Mauror, with some architectural remains from Arabic times still being visible on the right side.

It is made up of three arches, a middle one for carts and two others for pedestrians: the right one leads to Torres Bermejas, the Auditorio Manuel de Falla and Carmen de los Mártires, while the left one formerly known as the Cuesta empedrada (cobbled hill) leads to the southern flank of the wall of the Alhambra where there are various entrances to the Nasrid palace, the Puerta de la Justicia and the Puerta de los Carros. The middle arch, the largest one, gives access to a paved pedestrian path that was used for public and private transport, a road leading to Palacio de Carlos V, the church of Santa María de la Alhambra and the Parador Nacional de San Francisco.

Vermilion Towers

The Vermilion Towers or Torres Bermejas are from the Nasrid period. Due to its origins it is likely the oldest in Granada since it was located on the high hill overlooking the whole area. It is also where the Jews lived already in the early times of the Roman Empire. They were established in what currently is the Antequeruela and neighbourhood of Realejo. In the Muslim period it was the Jewish quarter or Aljama, which led to the name Granada, Garnata al-Yahud, the Pomegranate of the Jews.

So the castle of Mauror was both used for defence as well as for keeping watch and control. Three towers are what today remains from the castle, one larger one and two that are smaller, one defending to the east and the other to the west. In the Christian period a large artillery ravelin was built to the west to defend the castle.

From the castle the wall continued on to the south, encompassing Granada’s medina and the edge of Realejo, called rabad al-Fajjarin in Arabic times (the potters’ quarter).

Woods and Tajos de San Pedro

The woods and Tajo de San Pedro cover the northern and western area that surrounds the fortress of the Alhambra, bound by the wall connecting the Alhambra to the Tower of the picos and the general wall that surrounds the complex and which starts with the bastion of the Promenade Towers and which follows the bank of the river Darro.

To the east and west two gates were built in the 16th century, one below the Partal, next to the mill that was powered by the water from the stream in the ravine of the Cuesta de los Chinos hill or the Cuesta de los Molinos hill and the other on Cuesta de Gomérez, near the Pomegranates Gate, by the house of the Marquises of Cartagena, today called the Carmen de San Juan de Dios.

In the woods lies a wall which went down from the Gate of Arms until the bab al-Difaf (Puerta de los Adufes or Tableros en el Darro), although we do not know when it was demolished, it was rebuilt using brick. This fragment of the wall has two towers running to the east until Baba al-Difaf.

The hill of the Alhambra, as the location of the military fortress, lacked vegetation beyond the walls in order to aid in its defence, but upon Charles V’s arrival poplars were planted along the paths. It was not until the start of the 19th century when other types of trees were planted, such as horse chestnut trees, elms, plane trees…. which are still there today for visitors to enjoy.

Tajo de San Pedro

In Arabic times there must have been a defensive wall in this area, running along the river, which went around a cliff much smaller than it is in its present form.

The Tajo (cliff) is around 65 metres high and is located 24 metres from the walls of the Alhambra, abruptly cutting the hill and being a geological phenomenon similar to the Tower of Pisa.

Most of the damage was caused in 1590 when a powder keg exploded which was in the church of San Pedro and affected a number of dependencies of the Alhambra fortress, although over the centuries this “bite” out of the hillside has been increasing due to earthquakes, moisture and erosion of the Darro river.

Dryland

History of the Alhambra

The name Al-Hamra means “The Red” which refers to the colour of the earth on the hill of the Sabika according to Arabic authors.

The first structure to be built is clearly the Alcazaba, built in the Ziri period (11th century) in the time of the Taifa kingdoms on the peninsula. In the Almohade period (12th-13th century) it was called Al-Qasaba Al-Hamra (“the red alcazaba”) to distinguish it from the alcazaba in the Albaycin. The Alcazaba was preserved when renovations were done in the Nasrid period (13th to 15th century). It in this period, when Madinat al-Hamra came into being, the Alhambra’s medina.

In the history of the Alhambra we find three Muslim periods and two Christian ones that are clearly defined:

Christian periods in the Alhambra

The first period

It is considered to have started in the 15th century, a major change occurred in the medina of the Alhambra, since Christian and Muslim mindset are different:

In 1492 the Alhambra became the seat of the General Captaincy in order to control the massive Muslim population which lived in the medina of Granada and in the Albayzin.

The great mosque was made sacred, was turned into a church- the Iglesia de Santa María, the palace at the start of the street Calle Real Alta was turned into the Convent of San Francisco and work and preparation was undertaken for the Catholic Monarchs to be able to settle there.

The Palacio de Comares and Palace of the Lions were connected and were referred to as the “Casa Real” (royal house) since they were occupied by the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand themselves. The Count of Tendilla also carried out work in 1492 to modify the Arabic palaces for Christian needs.

The large cistern was also built between the Alcazaba and Calle Real Alta. Later on a number of gates and towers were fortified with artillery magazines which changed the inner and outer structure of the Alhambra’s medina.

In 1526, for the honeymoon of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, new preparatory construction work was done. However, the big change occurred when the decision was made to build the renaissance palace, the Palacio de Carlos V (Charles V).

The gate known as the Puerta de los Carros was also opened so carts loaded with materials could be taken up to the palace, and having laid the foundation of the new palace, the labyrinth of medieval streets was rendered obsolete. The same palace is located on the street Calle Real Baja blocking the medieval walkway to the Palace of the Lions and the Partal palace.

In the Renaissance period the Jardín de los Adarves garden was built on the large southern ditch of the Alcazaba, the Puerta de las Granadas/ Pomegranates Gate in the line of the wall that connects the Alcazaba, Torres Bermejas and the famous Pilar de Carlos V next to the Puerta de la Justicia, also known as the Puerta de la Explanada.

Second Christian period

From the 18th to 19th century, the Alhambra was completely abandoned which is reflected in the prints done by English and French artists. After the disaster brought on by the French leaving the Alhambra, between 1810 and 1812, when Ferdinand VII named the first architect to be in charge of its conservation in 1828, José Contreras, which started a long process which Modesto Cendoya followed; yet was finished with Leopoldo Torres Balbás when the work was finally completed, since the latter carried out countless projects in his time as Supervising Architect, from 1923 to 1936.

The Alhambra has been carefully attended to and handled over the course of the 20th century and the start of the 21st by all of the architects who have worked on it.

The combination of the Alhambra and the Generalife monumental complex, a World Heritage Site, is one of the most beautiful and complete monuments from the medieval Muslim legacy on the Iberian Peninsula. On top of its historical, architectural and decorative value, one revels in its aesthetics and our senses enjoyment of it.

The care taken in the restoration and preservation work carried out from the moment it was transferred into Christian hands at the end of the 15th century, and especially in the 19th, 20th and 21st century, makes it possible to admire and experience one of the most emblematic monuments of our past.

Muslim periods in the Alhambra

First period, from Muhammad I to his great grandson Nasr (1232-1314):

Muhammad I (1232-1272) undertook important renovations in the Alcazaba, which underwent a profound transformation compared to what it had been during the Ziri period, erecting a double wall among other construction work. In the Plaza de Armas there was also a major change with new multi-story towers such as Vela Tower or Torre de Homenaje and the military camp with the building of small brick homes.

Muhammad I also built the whole fortified perimeter of the Alhambra, linking the Alcazaba with the rest of the wall and reinforcing it with numerous towers such as the primitive Comares one which is smaller than at present and built into the wall, the primitive Tower of the Picos, which put the Alhambra in communication with the almunia (a type of Andalusian rural building) of the Generalife and the Torre de los Abencerrajes, together with the Justice Gate enclosing the perimeter.

In the period of his son’s rule, Muhammad II (1272-1303), the first great palace was built in the medina in the area called the Partal Alto. La Rawda or Royal Cemetary. It dates back to the time of Muhammad II since he was the first sultan to be buried there. The Palacio de los Abencerrajes also dates back to this time.

His son, Muhammad III (1303-1309), was the one who would really energise the urban development of the Alhambra. He is considered the urbaniser of the medina, giving it the essentials it needed for the city’s development. He built the Madraza de los Príncipes courtyard as well as the Patio de la Machuca. Below his father’s palace he built the Partal Bajo palace. Muhammad III built the Gate of wine in the street Calle Real Alta near the great mosque or aljama, as well as the Polinario public bathhouse. He also built the palace of the ex-convent of San Francisco, and the Medina of the Alhambra during this period, the medina also being known known as the artisan’s quarter of the Secano. Outside the grounds of the Alhambra’s medina Muhammad II built the almunia of the Generalife.

Nasr (1309-1314), the last sultan from this period, built a tower, the Tower of the Peinador de la Reina beside the old Tower of Comares.

In the second period, the dynastic change from the direct line to the secondary one with Isma’il I with it reaching its peak with his son Yusuf I and his grandson Muhammad V (1314-1392)

Ismai’l (1314-1325) built the Mexuar which would later become the Palace of Comares. It has new elements that mark the beginning of genuine Nasrid art creating the cubic capital.

With the arrival of Yusuf I, his son (1325-1354), the golden age of Nasrid art began. He’s the great builder of the Palace of Comares adding the first two courtyards built by Muhammad III to it as well as his father Isma’il’s Mexuar. He added a little mosque or praying chamber similar to the one in the Partal to the Torre de Machuca, with a phenomenal view looking out over the Albaycin. In the Partal Bajo there’s a small mosque and the towers, the Torre of Cadí and the Torre de la Cautiva. In the southern area, the door of the Siete Suelos was built, which provided access to the artisan quarter of the Secano. More importantly, it is the Jusice Gate, the bab Al-Saría.

Muhammad V (1354-1359/1362-1392) represents the height of this period and Nasrid art with the construction of the Palace of the Lions (1380). When Yusuf I died, his father took over finishing the work for the Palace of Comares and remodelled many parts of the medina which had been previously built by Muhammad III. He renovated the decorative work on the eastern façade of the Puerta del Vino and made major changes to the Mexuar hall.

The third and last period of Nasrid art is characterised by not following the proportional canon of the previous period. This period could be referred to as the one of decline (1392-1492). Little new construction was undertaken in the Alhambra.

Muhammad VII (1392-1408) was the last builder, adding the Torre de las Infantas next to the Torre de la Cautiva.

Yusuff III (1417-1429) only renovated the areas of some already existing palaces such as the Palacio del Partal Alto which was the work of Muhammad II.