Did you know that we owe much of the etiquette we use when dining to Ziryab, an Andalusi court advisor? And did you know that the way we use olives also derives from Al-Andalus? Or that sugarcane arrived in Spain thanks to the Muslims? At CICERONE, we are sure that you have heard about the strong Andalusi culture influence in our current society; but what was their real contribution to Andalusian and Spanish cuisine?

Índice de contenidos

Ziryab arrives in Córdoba and revolutionises andalusi cuisine

When you know the Mezquita in Córdoba or see the Alhambra in Granada you get an idea of the sophistication of the culture of Al-Andalus. rt and science meant everything to them. This is why scientists, musicians, artists and poets were the veritable celebrities in their culture. They insisted on supporting and nurturing talent and had no hesitation about inviting outstanding figures from abroad. However small, any contribution to Al-Andalus was valued.

Well, it turns out that one of the people invited was Abu-Hasan Ali Abn Nafi, also known as Ziryab (Blackbird). He arrived in Córdoba in the IX century, from Baghdad as a renowned musician and poet. Ziryab was a born observer and immediately came to the conclusion that there was a lack of refinement in the emirate’s cuisine. Despite the fact that the dishes had a profusion of ingredients, the recipes lacked finesse, as though eating was not also a sensory and aesthetic pleasure.

Thus, after conducting a meticulous study of what was being eaten, he discovered that the cuisine of the day had its roots in a mixture of Roman, Syrian and Berber cultures. They scarcely ate any fruit, the dishes were presented in haphazard fashion, heedless of how they might be arranged to emphasise their flavours, without any utensils… Being the talented and practical person that he was, and well-acquainted with the cuisine of Baghdad, he set to work and turned himself into the culinary advisor to the andalusí emir.

Ziryab, fundamental to the culinary legacy of Al-Andalus

It was then that Ziryab, the Blackbird, began introducing novelties that today seem indispensable. Can you imagine a cupboard without sugar? Strange, you will agree. The Blackbird advised that sugarcane should be grown more widely, which became an essential crop in the economic development of Granada in the Christian and contemporary era. Moreover, he transformed manners at the dining table: he introduced glass drinking vessels, tablecloths, the order of dishes… all of which are fundamental elements in homes throughout the world and, of course, in restaurants, particularly those that covet or aspire to a Michelin star.

But that’s not all. He replaced the coarseness of the recipes with elegance. His dishes were the most succulent and sophisticated conceivable. It’s a pity that we have to imagine them and it has not been possible to preserve his book of recipes, written in Arabic in 1260. We do however have a record of two andalusí recipes that are directly inspired by him:

Ziriabí

A dish made with roasted and salted broad beans, which could well have been the origin of two of the most iconic dishes in Granada’s cuisine: broad beans with ham and beans with cod.

Granada’s cuisine: beans with serrano ham

Beans with ham

It is very simple to cook, elaborated with beans, ham, and onions and eggs. This is a delicacy that melts in the mouth. What with the lusciousness of the beans and onions, together with the salt in the serrano ham and the viscosity of the egg… it’s too good to miss! It’s true that the serrano ham, coming as it does from pigs, would not have featured in the ingredients for Ziryab’s recipes, but it is equally likely that its inclusion was connected to this original salty taste. In Granada (Things to do in Granada), we usually eat it in spring.

Beans with cod

Aubergine tortilla

Despite the name, this does not refer to the typical tortilla of the Mediterranean diet. Far from it. This is an alternative that harbours a wealth of flavours and nuances. Would you like to know how to make it, in the words of Ziryab himself?

“Take some sweet aubergines and boil them in salted water until soft and well cooked. Drain the water, mash the aubergines and mix them on a plate with grated breadcrumbs, beaten egg with oil, dry coriander and cinnamon; beat until the mixture is consistent. Next, discs made with this mixture are fried in a frying pan with oil until golden. Make a sauce of vinegar, oil and crushed garlic; all of this is brought to the boil and poured on top.”

Agriculture and Andalusí cuisine: a legacy that survives to this day

As was mentioned at the outset, Al-Andalus is in the origin of our Spanish and Andalusian society. When the came here, besides building fortresses, schools and palaces, took it upon themselves to revolutionise agriculture and, by extension, the economy and the cuisine. They filled the fields with orchards, terracing, kitchen gardens and acequias, or irrigation channels, for watering the crops that they had brought from wherever they had settled earlier.

Can you guess which plants these were? Grains as essential for us as rice; vegetables such aubergines and spinach; spices such as cinnamon; and fruits such as oranges, acorns and, of course, pomegranates. All of these came from Asia Minor, Persia and Syria. A trick for identifying crops with an Andalusi origin is to look for fruit and vegetables that start with “al”. Indeed, although olive trees were already present on the Peninsula, the Spanish word aceituna (olive) is Arabic in origin. We also owe olive oil to them!

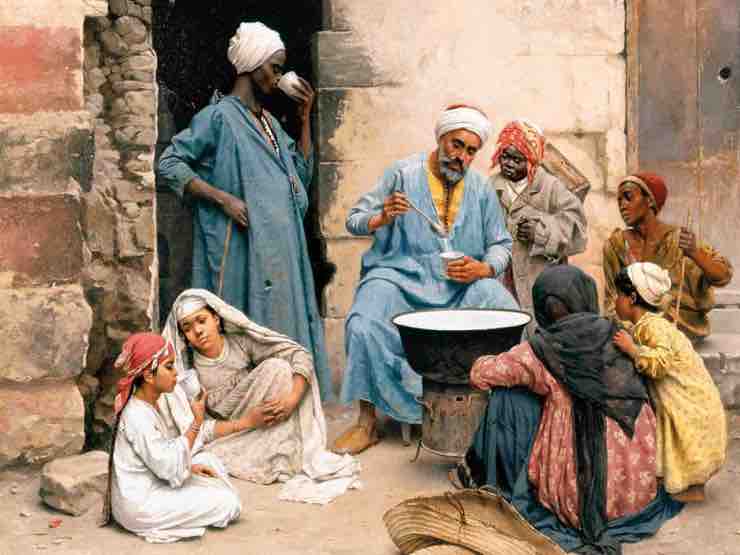

These products could be found in the zoco, or Arab market. Do you think that their innovations ended there? No. Fresh goods could be bought at the zoco, it’s true, but also ready-made dishes such as harísa and tarid. Discover the Dobla de Oro tour in Granada.

Andalusí cuisine is thus, in a way, Andalusian and Spanish cuisine. It’s a gastronomy that results from the contributions of all the cultures that have existed in this place and have been seen in our land, a place for putting down roots.